The part played by natural resources in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in Latin America and the Caribbean

Work area(s)

Topic(s)

A. Comprehensive analysis of the implications of COVID-19 for natural resources in Latin America and the Caribbean

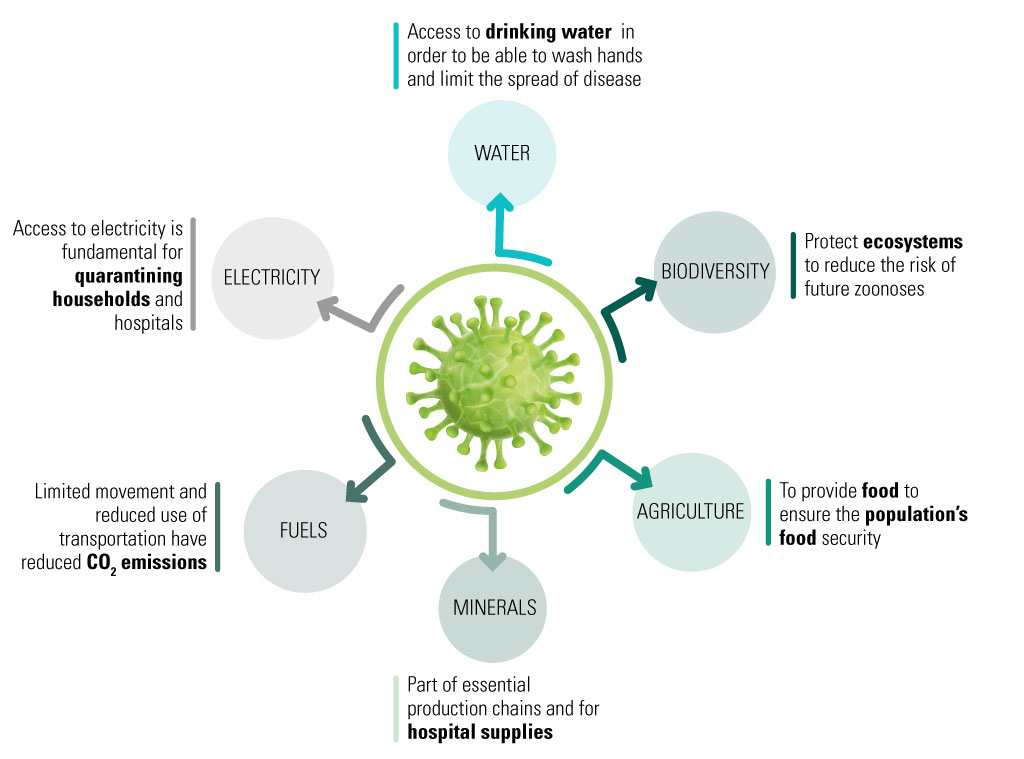

The COVID-19 pandemic has had enormous social and economic impacts on the region and across the globe. The direct consequences of the measures adopted by governments in the region to restrict movement are widely acknowledged, but no in-depth exploration has yet been conducted of the key relationships between natural resources and precursors, the spread of infection and the impacts of the disease itself. There is a very diverse set of relationships between natural resources and the COVID-19 pandemic (see diagram 1).

Diagram 1

Role played by natural resources in the COVID-19 pandemic

in Latin America and the Caribbean

Source: Prepared by the authors.

On the one hand, these resources (food, safe water, biodiversity and electricity) are vital for controlling the crisis; on the other, they are affected by the consequences of the crisis (the use made of fuels and minerals, for example). Access to drinking water is vital given that washing hands is one of the main steps that can be taken to avoid the spread of the disease; sources of power, including electricity, are essential to guarantee water supply and other conditions that make homes inhabitable, as well as to keep hospitals operational; agriculture underpins food security; and, lastly, non-renewable natural resources are of great macroeconomic importance in most Latin American and Caribbean countries.

Lockdown measures have triggered a temporary and steady decline in the use of fuels and, hence, in the emissions and contamination derived from them, as well as in the mining of those resources. COVID-19 is a zoonotic disease (that is one that can spread from animals to humans), but it has spread very easily from one human being to another because of overcrowding and the close connectivity built into our social structures. One of the problems with zoonotic diseases that has so far received relatively little attention is that natural barriers to them continue to be pushed back, as the ecosystems capable of controlling the spread of diseases continue to be fragmented, degraded, and destroyed. All studies exploring the reasons for the spread of zoonotic diseases identify land-use change as the principal cause (Gottdenker and others, 2014). The five leading factors are: land-use changes (fragmentation and degradation of ecosystems); food industry changes; human susceptibility; and international connectivity (travel) (Suzán, 2020). A high level of species diversity, which is a characteristic of healthy ecosystems, regulates the population of those species that act as primary reservoirs of viruses, thereby curtailing the transmission of pathogens. The evidence indicates that conserving biodiversity and its ecosystem services is necessary to protect human health both directly and indirectly.

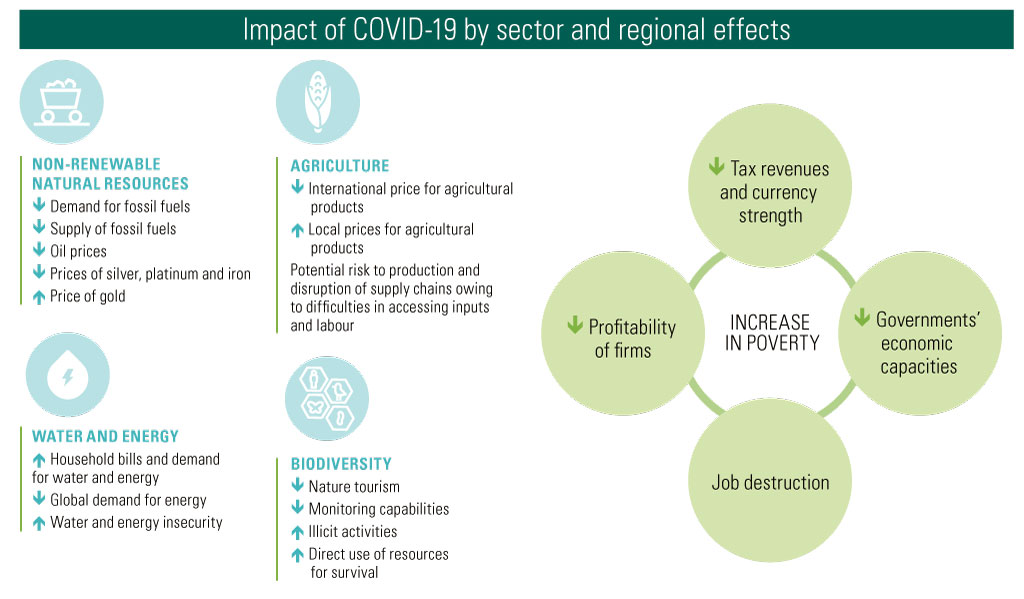

Measures to halt the spread of COVID-19 have affected natural resources and have had a severe economic impact, hitting the most vulnerable social sectors in the region hardest. Among the most notable impacts observed are a drop in world prices for fossil fuels, minerals, and agricultural and livestock export products; a fall in the demand for energy; a decline in corporate profits; lower tax revenues; and a weakening of currencies in the region. As a result, governments’ ability to manage the economy is diminished, undermining efforts to tackle the pandemic and its economic and social impacts. All that increases poverty and extreme poverty in the region, in a context in which the number of those infected by the disease continues to increase with no certainty as to when that number will peak.

Moreover, the impacts described above are seriously hampering efforts to attain the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. It is therefore crucial to guarantee sustainable economic recovery, so that progress can continue to be made toward achieving the SDGs related to natural resources management, in particular: SDG 6 (ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all); SDG 7 (ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all); SDG 2 (end hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture); SDG 14 (conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development); SDG 15 (protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, halt and reverse land degradation, and halt biodiversity loss). Thus, post-pandemic recovery measures should focus primarily on reducing social and environmental vulnerability in the medium and long term, thereby lowering the risk that future complex scenarios will have impacts as severe as those being felt today.

Diagram 2

Impacts of COVID-19 on natural resources and their economic and social consequences

Source: Prepared by the authors.

B. Sectoral analysis

1. Access to safe water and electricity

To halt the spread of the global pandemic, most countries in the region have implemented lockdowns and physical distancing measures that have affected millions of people. Under those circumstances, access to drinking water and electricity is vital. However, inequitable access to these services in the region has exacerbated the impact of the crisis, especially on the most vulnerable. Compliance with mandatory quarantines is particularly difficult for households with no or only intermittent access to water and/or electricity. That makes it all the more pressing for governments to ensure the availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all (SDG 6), together with access to affordable, reliable and sustainable energy for all (SDG 7). Shortfalls in or the absence of such services can trigger a cycle of deprivation with serious repercussions.

Access to drinking water is essential for tackling the pandemic, given that frequent hand washing has proved to be one of the most effective ways of slowing the pace of infection. Over one quarter (26%) of the population of Latin America and the Caribbean (166 million people) lack adequate and permanent access to drinking water, or to water inside their homes. That percentage is 58% among the rural population (JMP, 2020).

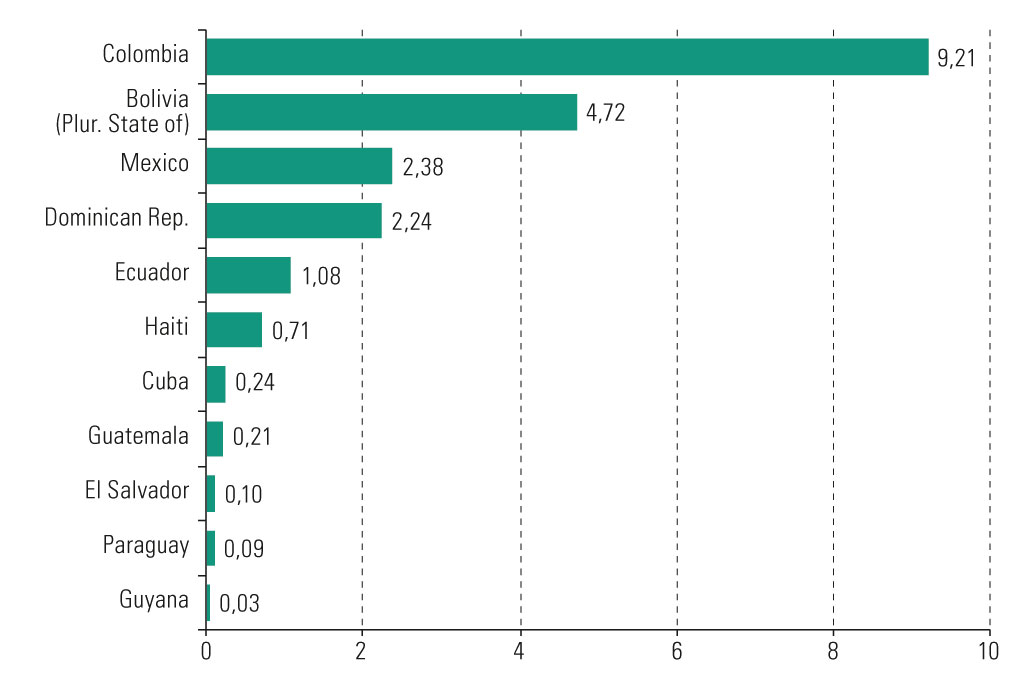

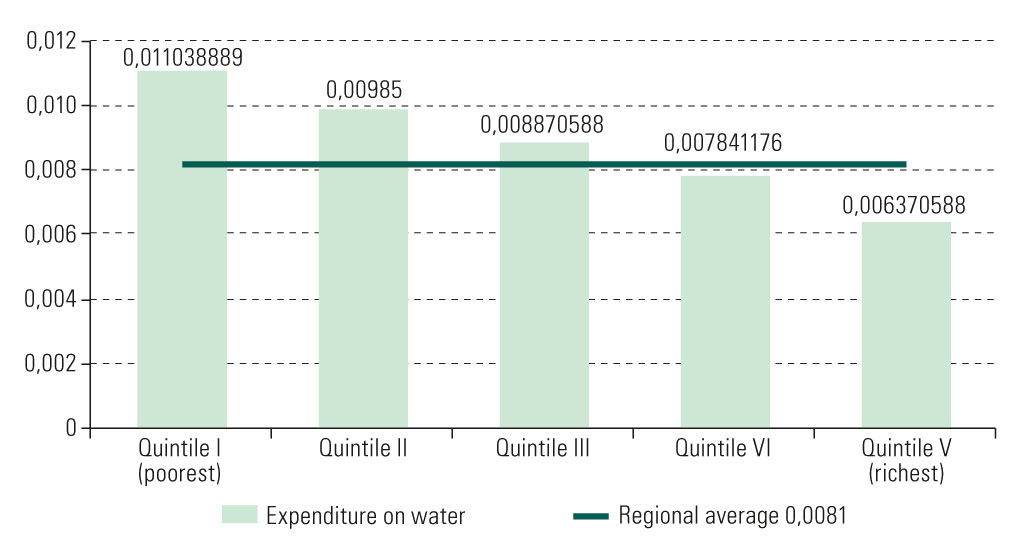

At the same time, 80% of the region’s population lives in large cities in which social interaction implies an increased risk of infection, especially in the most densely populated districts, which also tend to be the most vulnerable. Although rural populations are more vulnerable with respect to access to good-quality drinking water, in absolute terms the number of people without access to hand-washing facilities at home in cities is alarming: more than 9 million people in Colombia, almost 5 million in the Plurinational State of Bolivia, and at least 2 million in Mexico (see figure 1). Lastly, the percentage of total household expenditure on drinking water services in the region by lower income quintiles is double the share of the richest quintiles (see figure 2). This is especially important in a global context of huge economic shocks that will most likely lead to massive job losses and many households being unable to pay for utilities.

Figure 1

Latin American and Caribbean (selected countries): urban population without access to hand-washing facilities, 2017

(Millions of people)

Source: WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene (JMP), The JMP Global Database, 2020 [online database] https://washdata.org/data/household#!/table?geo0=region&geo1=sdg.

Figure 2

Latin America and the Caribbean: average expenditure on water by income quintile,

latest available yeara

(Percentages)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of data from household surveys.

a Data for latest available year: Argentina (2012), Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela (2008), Brazil (2008), Chile (2012), Colombia (2007), Costa Rica (2013), Dominican Republic (2007), Ecuador (2014), El Salvador (2006), Guatemala (2014), Honduras (2004), Mexico (2012), Nicaragua (2014), Panama (2007), Paraguay (2011), Peru (2014), Plurinational State of Bolivia (2013) and Uruguay (2006).

Access to electricity is also essential. Not only is it vital for a variety of health-care services, it also guarantees better living conditions in households (including lighting, refrigeration and heating). In addition, water supply is heavily dependent on electric power for its extraction, purification and distribution.

Although most countries in the region have high rates of access to electricity, 18 million people are still not connected to the grid, a fact that, during pandemics, exacerbates existing inequalities and vulnerability (see figure 3). This energy insecurity has a daily impact on people’s physical, social, and economic conditions: above all, those needed for survival.

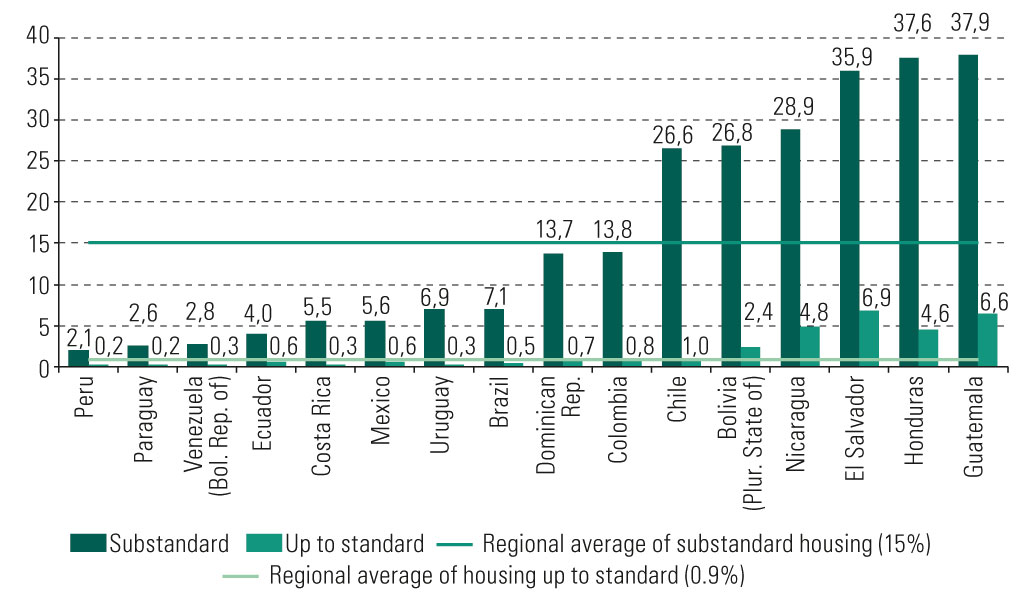

Figure 3

Latin America (selected countries): national average of the population without access to electricity by housing standards, latest available yeara

(Percentages)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of Household Survey Data Bank (BADEHOG).

a Data for latest available year: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Paraguay, Peru, Plurinational Republic of Bolivia and Uruguay, 2017; Dominican Republic, Honduras and Mexico, 2016; Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Guatemala and Nicaragua, 2014.

Note: Population-weighted average.

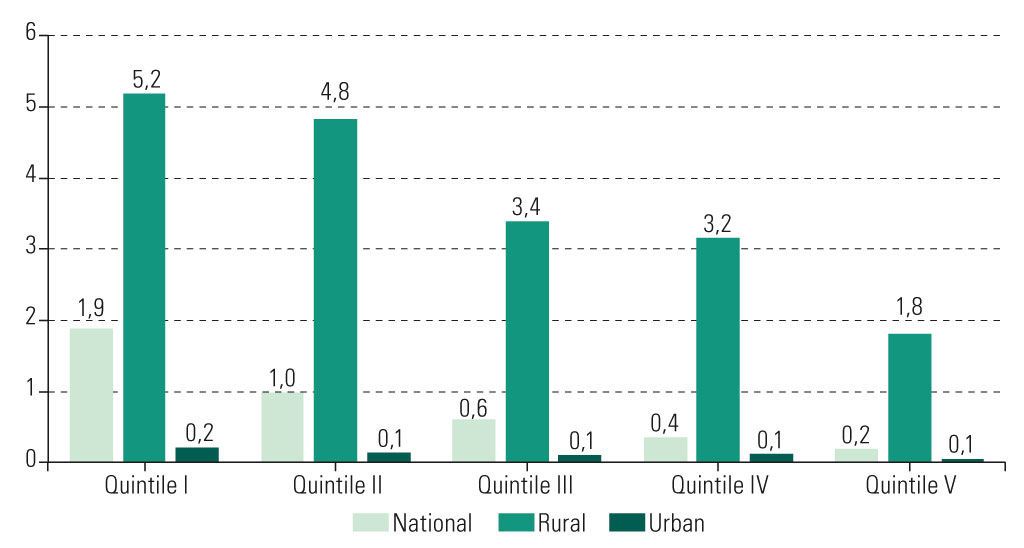

Most of those without access to modern electricity services live in rural and extremely poor areas (quintile I). The population without access to electricity is three times larger than the rural population in the wealthiest quintile and triple that in the poorest quintile (see figure 4).

Figure 4

Latin America (selected countries): rural, urban and total population without access to electricity by income quintiles, latest available yeara

(Percentages)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of Household Survey Data Bank (BADEHOG).

a Data for latest available year: Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Paraguay, Peru, Plurinational State of Bolivia and Uruguay, 2017; Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Mexico, 2016; Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Guatemala and Nicaragua, 2014.

Note: Population-weighted average.

Public utility authorities have reported considerable increases in household demand for drinking water and electricity, as a result of quarantines, telework and efforts to combat the pandemic, among other factors. That has led to increased spending on those services by households whose payment capacity has, in many cases, declined because of unemployment or lower wages.

On the other hand, containment measures to control COVID-19 have impacted industrial production and reduced its demand for electricity. In Chile, during the month of March 2020, the demand for electricity from the industrial sector had already fallen by around 3.8% compared to the week before the appearance of COVID-19 in the country, and dropping during the month of April to approximately 6%. This situation will in no way be compensated for by the increase in demand for electricity in homes, since the decrease in electricity demand due to the containment of much of the industrial sector is several orders of magnitude greater. Total demand is expected to continue falling, on average by between 15% and 30%, forcing electricity generating and distribution companies to adapt to this new pattern of supply and demand. Electricity generation, transmission and distribution companies tend to have established contingency plans to enable them to operate effectively following natural disasters, cyberincidents and power outages, among other events. However, most enterprises in the electricity sector lack contingency plans for dealing with the situations arising from the pandemic, such as quarantining at home, prolonged shutdowns of critical infrastructure (local means of transportation, for example) and the additional travel restrictions that may occur in the event of a health emergency.

At the same time, in the electricity and renewable energy sector, the macroeconomic impacts of COVID-19 will also affect companies that were in the process of implementing generation projects. Renewable energy projects in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Mexico will be hit especially hard as they face steep and unexpected increases in the cost of capital, due in large part to the depreciation of regional currencies against the United States dollar and the euro. The repercussions of this will make it difficult to achieve renewable energy output targets set for 2020 and 2021, and to attain SDG 7.

To mitigate the economic impact on households, the governments of the region have opted to lower electricity consumption charges, introduce more flexible payment arrangements and prohibit the termination of service for non-payment. The implementation of these measures should contemplate oversight mechanisms to deter those who can afford to pay for service from stopping their payments, so as to reduce potential management, liquidity and sustainability issues for suppliers. What those measures do need to accomplish is guaranteed access to drinking water, sanitation and hygiene for the most vulnerable segments of the population. The impact of these measures on the economies of the region are still uncertain and must be assessed in the short, medium and long term. That will require monitoring of the actions undertaken and forward-looking evaluation of the results of their implementation.

In light of the situation described above, the main recommendations for Latin America and the Caribbean may be summarized as follows:

- Continue the measures adopted by several Latin American and Caribbean countries to facilitate the payment of water bills, paying particular attention to the most vulnerable groups and health-care facilities. For the population without access to safe drinking water, establish alternative, expeditious forms of access, such as the use of water trucks. Here there needs to be a focus on small-scale water suppliers and people living in rural areas, with a view to avoiding widespread infection in those areas, which tend to be far away from health-care facilities.

- Assess the impacts on the most vulnerable, and energy and water poor populations, and develop inclusive, solidarity-based tools and policies geared towards cushioning the impacts of this crisis on the budgets of the most vulnerable households.

- Develop or strengthen water bill subsidies and identify vulnerable groups so that these subsidies are directed toward those who need them most (thereby making better use of countries’ limited financial resources).

- Engage in joint actions between governments and energy and water companies to ensure the supply of these services. It is especially important to guarantee companies’ access to liquidity and households’ access to income.

- Bolster the role of the State as guarantor of the right to access basic services —drinking water and electricity— through a public-private cooperation mechanism that seeks to forge a more inclusive, solidarity-based and equal economic system that puts everyone on an equal footing.

- Prioritize public policies, actions and investments aimed at providing more effective access to drinking water and sanitation. That means moving towards the universalization of (better and more efficient) water and sanitation services, including sewage and wastewater treatment services. All of the above yield huge benefits in terms of efforts to promote public health, combat poverty and extreme poverty, foster sustainable development, reduce social conflicts and protect the environment.

- As an additional long-term support measure, and with a view to attaining the objectives of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, cooperation agencies and international and regional banks should focus on improving access to drinking water in Latin American and Caribbean countries.

- Focus on financial support efforts, especially access to soft loans, so as to be able to step up implementation of renewable energy projects. This would help facilitate the continuity of energy supply in the event of future pandemics, since renewable energies, such as solar energy and wind power, can be operated remotely and reach outlying rural areas. Thus, capacities can be built to respond more effectively to other kinds of extreme events or disasters.

- Recognize the benefits of energy complementarity and integration at the regional level. Complementarity and developing regional energy integration will enhance the reliability of energy supply and help stabilize electricity prices, while extending those benefits to countries of the region that are less well endowed with hydroelectric power.

2. Agriculture and food supply

The pandemic is having a marked impact on both the production and consumption of agricultural produce. On the demand side, it is reducing food security, due to the loss of jobs and declines in wage income. The number of persons in the region living in extreme poverty, which correlates closely with hunger, is expected to increase by nearly 29 million (ECLAC projection made on 9 July 2020). On the supply side, the pandemic is putting pressure on every link in the agricultural sector supply chain, from harvesting through to final consumption.

The pandemic is, however, occurring in a relatively favourable agricultural context , in which stocks of the basic grains have increased. As a result, at the start of the crisis, the global food system was well supplied with the main staples, thanks to the accumulation of stocks and good harvests in South America and other parts of the world (OECD, 2020). Prior to the COVID-19 crisis, prices had also been relatively stable since mid-2016, following high-price periods between 2011 and 2015, and highly volatile prices between 2007 and 2011. Fertilizer prices have been trending down since end-2018.

The emergency has lowered international prices for most staple products. On average, between January and April 2020, international food prices fell by 9.1%, compared to drops of 12.5%for minerals and 47.9% for energy. The general price trend for most foods is downward. The only product for which prices rose between January and May 2020 was rice (15.7%), which is also a pillar of food security. In contrast, prices of wheat and maize fell -8.3% and -16.2%, respectively.

At the national level, however, COVID-19 has increased the risk of future volatility in food prices. As of May 2020, the food price index had increased almost four times faster than the general price index in the region. This increase occurred mainly during March and April, when lockdown measures began to be implemented in most countries, triggering increases in demand and uncertainty in supply. In most countries, the increase tapered off in May, as uncertainty decreased and countries started or stepped up food distribution programmes.

By its very nature, the food sector can adapt better to the crisis than other sectors. Unlike the manufacturing sector, its global value chains are simpler, shorter, and more resilient. In general, food products are produced by single-country companies, have few (or replaceable) components, and, when they are exported, incorporate services provided by a small number of foreign (insurance, shipping, marketing and other) companies. This stands in contrast to global value chains for other geographically dispersed industries, in which products cross multiple borders before reaching the end consumer.

However, there are risks of disruptions to the food chain. Each link in the production chain has had to adapt in order to stay operational. The principal challenge facing regional governments is preventing the pandemic from turning into a food crisis.

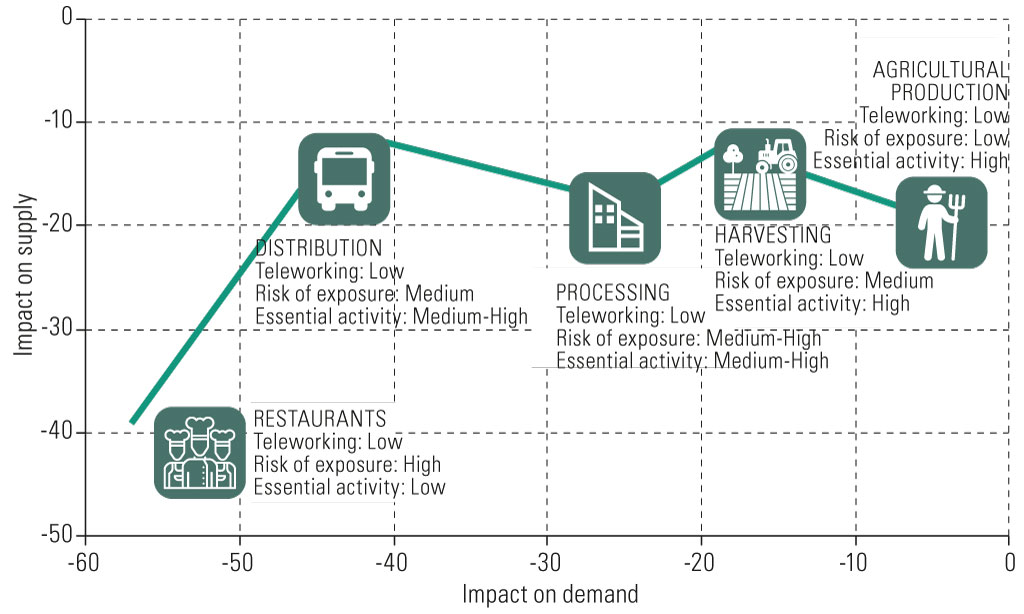

Some links in the chain (such as processing and end-sales in markets) have been identified as sources of COVID-19 outbreaks because they are both essential and highly exposed (see figure 5).

Figure 5

Impact of COVD-19 on a number of food supply-related activities,

in terms of supply and demand

(Percentages)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of D. Farmer and others, “Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic”, CEPR Covid Economics, 17 April 2020.

The decline in employment associated with the impact of COVID-19, along with the rise in food prices, is highly likely to increase poverty, extreme poverty and hunger. The number of people living in extreme poverty could increase by 28.5 million in 2020 to total 96 million, 35 million of whom reside in rural areas.

In that context, and with a view to solving the pandemic-related problems affecting the agri-food sector, recommendations for governments of the region include:

- For householdsguarantee access to food for the most vulnerable segments of the population immediately as a basic measure. In this regard, ECLAC has pointed to the need for an anti-hunger grant. The value of each grant would be equivalent to 70% of the regional extreme poverty line (US$ 67 at 2010 prices). The total cost of the anti-hunger grant is estimated at US$ 27.1 billion, or 0.52% of regional gross domestic product (GDP) (ECLAC, 2020a). It would cover all those living in extreme poverty in 2020. However, this type of transfer generally poses operational problems in all countries. That being so, it is suggested that part of these funds be used to expand school feeding programmes and/or food aid to households, which serve to direct food assistance to the most vulnerable families. All this requires the support and participation of local communities, food sector companies and other civil society actors.

- For supply chains: make sure that food supply chains continue to function, by maintaining and expanding financial support policies for companies so that farmers, and food sector and service companies can continue operating uninterruptedly.

- For producers and enterprises: ensure the continuity of food output, especially by family-run and indigenous farms. One proposal is to increase soft loans managed by multilateral and national development banks (by US$ 5.5 billion, or 20% of the portfolio). For the least developed or financially underserved farms, a non-reimbursable investment is suggested (in the form of a basic investment kit for 6.8 million farms, with a total cost of US$ 1.7 billion). The former would be managed by multilateral banks and national development banks.

In this context, the agricultural sector needs “to build back better”. The decline in fiscal resources and sheer magnitude of the problems to be addressed will make it necessary to rethink post-crisis public policies for agriculture and rural areas. Across the board, new agricultural and rural development programmes are needed to deal with the emergency and its economic repercussions, as well as to expedite the process of climate change adaptation. The crisis should serve as an opportunity to foster changes in the global food system. The pandemic reaffirms the need to transition towards more inclusive and sustainable production models, promoted through broad political agreements and finely-tuned public policies.

3. Biodiversity

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected biodiversity in various ways and, although, generally speaking, evidence is limited, there are illustrative cases with regard to tourism, the illicit exploitation of natural resources, weaker observance of environmental standards and a possible reduction of the fiscal budget.

- The natural heritage in Latin America and the Caribbean is very important for tourism, which has declined sharply as a result of lockdown and prevention measures and border closures. A comparison of international tourist arrival statistics between May 2019 and May 2020 shows a 51-percentage-point drop in Chile (INE/Office of Tourism, 2020) and 73-percentage-point decline in Mexico (INEGI, 2020).

- The impact of COVID-19 on tourism in the region has cut the sector’s contribution to GDP and employment, and, in some cases, hampered the maintenance of national parks (ECLAC, 2020b). In Peru, for instance, a large part of the budget of the National Protected Areas Service (SINANPE) comes from fees paid to visit Machu Picchu.

- In Costa Rica, in 2016, tourism’s direct contribution to GDP was an estimated 6.3% (including indirect contributions, its share was 8.2%). In 2018, 44% of the budget for Costa Rica’s National System of Conservation Areas (SINAC) stemmed from resources generated by SINAC activities, including tourism (which accounted for 28%).

- The countries in Tripadvisor’s travel experiences ranking that have three or more natural parks and nature attractions are: Antigua and Barbuda, Argentina, the Bahamas, Barbados, Brazil, Costa Rica, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guyana, Jamaica, the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago.

Another negative impact on ecosystem health stems from the increased illicit exploitation of natural resources (logging, trafficking of exotic commercial species, mining, fishing, among other activities) by illegal armed groups and regional mafias who are taking advantage of more lax inspection, guardianship and defence of territorial rights because of lockdown measures. In Brazil, deforestation has increased by 64% compared to January–April 2019 figures, according to the National Institute for Space Research. Moreover, according to Rajao and others (2020), just a few (2%) of agricultural estates in El Cerrado and Amazonía are responsible for 62% of all potentially illegal deforestation. Colombia, where deforestation rates had declined significantly from 2018 to 2019, saw an upsurge beginning in 2020 (López-Feldman and others, 2020).

As poverty increases, the subsistence strategies of local communities that depend directly on surrounding resources for their survival are sure to result in higher consumption of firewood, food, traditional medicine ingredients and self-employment materials.

Some environmental measures adopted by several countries of the region have been relaxed or put on hold for health reasons, such as the rules on single-use plastics in the Caribbean, these countries had been at the forefront of such endeavours because the Caribbean sea is the second most plastic-contaminated sea in the world, and Chile’s rules on plastic bags and utensils. Although there is currently no conclusive evidence, regional news articles indicate that traditional economic sectors, such as infrastructure, mining, agriculture and so on, are exerting pressure on governments to relax certain environmental regulations or environmental impact assessments that they regard as merely bureaucratic hurdles, arguing that eliminating them will help “reactive the economy more quickly”. Nevertheless, it must be borne in mind that “cheap may be costly”, and if behaviour is not changed and ecosystem imbalances grow, the consequences in terms of both costs and social well-being may be far greater.

State budget cuts caused by the pandemic-induced economic crisis will probably hit hardest in 2021, given that in some countries this year’s budget appropriations will probably only undergo limited modifications. That said, there are already some countries in which cutbacks are already being felt in activities run and personnel hired by the State, especially in the environmental sector. In Mexico, the Federal Public Administration’s operational outlays have fallen by -75%. In Ecuador and Uruguay, the new institutional arrangements with regard to the environment that are designed to trim down the size of the State, have, in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis, affected both the number of workers involved and the budget. In the case of Ecuador, this was as a result of merging environmental institutions with those of the former Secretariat for Water, which will receive US$ 32 million this year, compared with the combined total of a little more than US$ 45 million in 2019. In the case of Uruguay, the establishment of a Ministry of the Environment brought about a 15% reduction in operating costs and a 40% cut in personnel contract outlays.

Another reduction in State revenue in the environmental sector is due, as mentioned earlier, to the fall in the number of visits to national parks, so a budget cut would make it harder not only to keep on the personnel involved, but also to maintain those sites as sustainable development hubs.

Below is a summary of some recommendations for Latin America and the Caribbean:

- Transitioning to a sustainable economy will yield significant benefits that exceed the investment costs involved. Economic and financial incentives should include valuations of nature as a profitable asset (in addition to its intrinsic or de facto value) and give due consideration to the negative externalities of natural resource extraction. The protection and sustainable use of natural resources can generate jobs and economic growth through tourism, agriculture and aquaculture, among other ecosystem services, and may generate five times more income than what their annual cost.

- It is recommended that efforts to conserve nature should not be eased because of post-pandemic economic imbalances, given that there is a real danger of losing ecosystem service benefits, possibly forever.

- The crisis should serve as an opportunity to rethink the interconnections between ecosystems, human beings and various parts of the planet. Part of the current crisis (the environmental imbalance and inequality in health and social well-being) predates COVID-19 and only by addressing its direct and underlying causes will we be able to forge a more secure future.

- The United Nations comprehensive approach to health (which examines the interrelationship among the health of human beings, domestic animals and ecosystems) should serve as a guide for the future. Investing in prevention is less costly than treating and curing diseases.

- Interfaces need to be forged between science, evidence and decision-making in the planning and implementation of solutions. Particular importance needs to be attached to monitoring short- and medium-term environmental impacts.

4. Non-renewable natural resources

In many countries in the region, extractive industries, including the mining of minerals and fossil fuels, have been exempted from restrictions imposed due to the pandemic, because they are initial links in supply and value chains. In many cases, they are key activities for the economy as a whole. For that reason, they have not been shut down completely. So, a large number of active projects are continuing to operate, albeit with more limited capacity and despite being subject to disease prevention measures and health-care protocols. New projects have however been suspended or postponed.

Despite that mixed picture, the large-scale containment measures implemented worldwide (such as border closures and mandatory quarantines), in an almost synchronized fashion, are having a profound economic impact. That translates into a slowdown in extractive activity, with restrictions on both supply (owing to closures and interruptions in global supply chains) and demand (owing to sharp declines in expenditure in the tourism, recreation, retail and transportation sectors leading to massive revenue losses). These effects on both aggregate and sectoral supply and demand have caused international commodity prices to fall, which is particularly serious for the economies of the region.

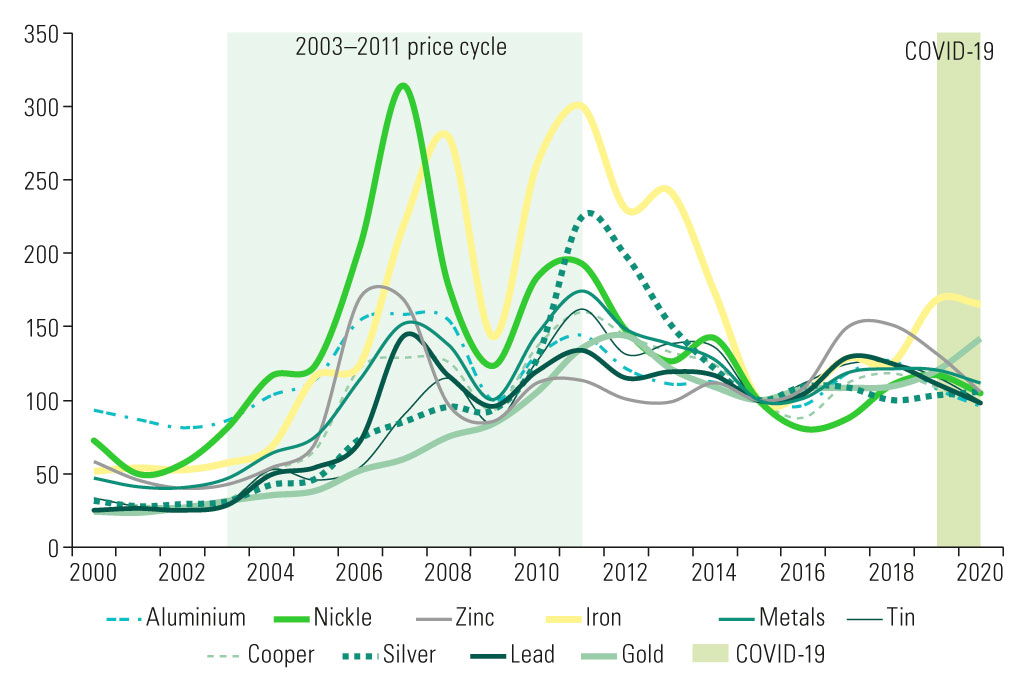

With the notable exception of gold, most mineral prices were trending downwards until June 2020 (see figure 6). As for fossil fuels, the steep drop in the price of oil has translated into lower gasoline prices. Against this backdrop of generally falling prices, together with lower external demand and a downturn in production, tax revenues and the availability of foreign exchange will decrease in countries whose economies depend on the exploitation of those resources. That, in turn, will, in the short term, reduce the capacity of their governments to respond to the pandemic and boost the economic recovery. Those countries that have accumulated savings and stabilization reserves, thanks to revenue directly or indirectly derived from non-renewable (extractive) natural resources, will be in a better position to support that sector during the crisis and to finance part of the expenditure needed to address the health and social emergency, as well as subsequent economic recovery.

Figure 6

Changes in price indices for metallic minerals and fossil fuels, 2000–2018

(Base year 2015 = 100)

A. Metallic minerals

B. Fossil fuels

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of “World Bank Commodities Price Data (The Pink Sheet)”, June 2020 [online] https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/commodity-markets.

Note: Annual values of the indices; the value for 2020 corresponds to the month of June.

With regard to the supply of and demand for oil and its derivatives, measures to contain the pandemic have also affected the production and consumption of fossil fuels. Global and regional supply and demand both fell in the first months of 2020 compared to the previous year. Demand has fallen faster, and at an unprecedented rate, while supply was partly sustained by a price war, which led to a surplus of output and pushed prices down until the world’s major oil producers reached an agreement. The April 2020 agreement to reduce output brought the dispute to an end, but could not prevent the crude oil price plummeting to a record low, as futures contracts close to maturity were closed out and a frantic search began for places to store surplus oil. The agreement reached between the member countries of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and their allies, including the oil-producing countries of the Group of 20 (G20), such as Canada, the United States and Mexico, (known as OPEC+) is considered historic, as it established a cut in production by OPEC+ countries of 9.7 million barrels per day during May and June 2020, equivalent to 10% of current global output. The countries outside OPEC+ were also expected to reduce production, although exact figures on the extent of their commitments are not yet available. There is still considerable uncertainty in the global market, with one projection estimating that a cut in production closer to 20% will be needed to reduce the gap in the coming months, depending on storage capacities (for strategic reserves, for instance) and on a recovery in demand (for example, if there is no second wave of the pandemic).

These arrangements have implications for the oil-producing countries of Latin America and the Caribbean. How much they produce is based on a barrel price higher than the current one and that projected for the next few months. Companies’ profitability will be lower in the short term, leading to cuts in investment and jobs. Their ability to make further efficiency and cost savings through technology and process improvements is limited because companies have already made considerable efforts in recent years.

Pandemic-containment measures have also affected global supply of and demand for minerals. Demand shrank after December 2019, albeit by less, and at a lesser pace, than it did in the case of fossil fuels. Meanwhile, supply slowed in the first months of 2020 but subsequently picked up again in March and April, thanks to a gradual return to activities in China and other Asian countries. This was evidenced in inventory changes (stocks, inflows and outflows) of the non-ferrous metallic mineral deposits in two of the major markets, namely the London Metal Exchange (LME) and the Shanghai Futures Exchange (SHFE). It should also be noted that, first, the global scenario for minerals prior to the pandemic was not promising either: China, the number one purchaser of minerals in the world, was in the midst of a trade dispute with the United States and its growth rate was slowing, limiting its demand. Second, the state of the industry and of the markets for each mineral prior to the pandemic was uneven, so the degree and extent of the impact of the economic downturn could vary for each mineral. For example, demand for gold and its price have stayed firm, whereas prices for silver, platinum and iron ore, which were trending upwards in the first quarter of 2020 compared to 2019, have experienced a cumulative decline between January 2020 and June 2020. Finally, the reactivation of China’s economy will depend on a recovery in both domestic demand and external demand for its products.

The region of Latin America and the Caribbean, which comprises a number of economies that are dependent on the production and sale of metallic minerals, such as copper, silver, gold and, to a lesser extent, tin, iron and zinc, is also relying on China’s economic recovery, as its main trading partner for those resources. China’s economic activity contracted in the first quarter, as was reflected in its minerals manufacturing sector, specifically its copper smelting and refining operations, and the accumulation of its stock of steel products: year-on-year changes in both cases show steep declines. Moreover, a glance at the changes in the production and export of copper in Chile and Peru and of iron ore in Brazil, confirms the drop in activity and flows, albeit with a slight time lag, given that the lockdown measures that brought supply chains to a standstill were applied in the region later than they were in China. Companies in the region have also started to reduce investments (mainly in development, equipment and exploration) and cut jobs (to varying extents, depending on the country and size of enterprise).

Lastly, one problem that has been exacerbated by the current situation is informal and illegal mining. Under current circumstances, this problem could grow and have numerous negative impacts on communities and territories.

In this context, and with a view to solving the pandemic-related problems that affect the non-renewable natural resources sector, some recommendations for the region include:

- Increase efficiency and lower costs by using new technologies. For this, government support is needed, particularly to revitalize and steer investment, in such a way as to minimize the impact on formal employment.

- Guarantee extractive industry operations in those countries in which they are vital for the economy, without compromising the health of workers and communities in the affected areas . At the very least, that means ensuring that transportation and communications function in the territories in which projects are located, and standardizing and monitoring health and other care protocols in the companies involved and in neighbouring communities, paying particular heed to indigenous communities.

- Avoid unnecessary tax relief and environmental, labour-market and tax deregulation.

- Reinforce inspections of compliance with environmental regulations and those related to social commitments in the territories hosting non-renewable natural resource extractive operations.

- Build capacities to monitor and control any informal and illegal mining operations that might be carried out in those territories, both during and after the pandemic.

- Initiate a process to evaluate extractive resource governance in order to improve or develop the institutional frameworks and skills needed to better manage the price volatility of these commodities; to enhance commodities’ value added through technological progress and production chain innovation; and to plan government budgets and decouple them from the exploitation (economic revenue) of these resources. Examples of such institutions are sovereign wealth funds (for stabilization and/or savings and investment), investment promotion agencies, development and innovation agencies, and public-private partnerships, such as technology centres.

3. Conclusions and main public policy recommendations

Keeping the activities of each of the analysed sectors going is essential to preserve livelihoods and tackle the pandemic. The State has a key role to play in providing the measures required to ensure that these activities can be conducted in a safe environment. It is recommended that the governments of the region take into consideration the difficulties that society faces as a result of the pandemic and that it act as a facilitator, fostering the establishment of programmes and policies that are mainly aimed at helping the most vulnerable segments of the population and that guarantee their water, food and energy security.

Below are the most important courses of action for each of the sectors analysed in this bulletin.

- The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its biodiversity, water, energy and nutrition targets are even more important today. The pandemic has reinforced the need to protect biodiversity, and makes it even more pressing to respect and protect natural habitats, and to ensure the sustainable provision of their services to the population. It is possible for economic recovery to be pursued in a manner consistent with the recovery of healthy ecosystems, but for that structural changes are needed.

- Promote the role of the State as the guarantor of basic water and energy services, with powers to prioritize the most vulnerable. The State plays a key role in fostering public policies for the provision of basic services; crafting subsidies with which to pay the most vulnerable households’ bills; and, together with providers, ensuring the continuity of supply.

- Guarantee access to food for the most vulnerable segments of the population by strengthening food programmes, with State financial support and the commitment of all civil society. It is also necessary to ensure that food supply chains function properly, based on the establishment and consolidation of financial policies to assist farmers and the food industry. A further recommendation is to foster a transition towards new production models that are more sustainable, inclusive and adapted to climate change.

- Guarantee the operation of activities related to non-renewable natural resource extractive industries in those countries in which they are vital for the economy, while safeguarding the health of workers and of the inhabitants of neighbouring communities. Avoid unnecessary tax relief and environmental and social deregulation, and reinforce inspection measures aimed primarily at preventing illegal activities. Lastly, it is important to promote the development of new technologies to make processes more efficient, resilient in the wake of emergencies and sustainable.

- A key factor, linked to all the foregoing recommendations, is to combine efforts to preserve ecosystem diversity and integrity, respecting their natural frontiers and avoiding the fragmentation, degradation and destruction of habitats. That is an essential task to protect human health, as it controls the spread and curbs the rise in zoonotic diseases.

- Education and awareness are key factors for bringing about a paradigm shift in the appreciation of natural resources. The pandemic has established a dividing line between essential and non-essential goods and services. One notable result of that division is that the pre-pandemic value attached to an activity may not match that attached to it during or after the COVID-19 pandemic (for example, the lowest-paid workers are now among the most essential), while what is essential (food, health, clean water) often depends on the sustainable use of natural resources and biodiversity.

Bibliography

Actualidad Ambiental (2020), “¿Es posible plantear una nueva moratoria para transgénicos en agricultura?”, 3 July [online] https://www.actualidadambiental.pe/es-posible-plantear-una-nueva-moratoria-para-transgenicos-en-agricultura/.

BlackRock (2020), “A Fundamental Reshaping of Finance” [online] https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/investor-relations/larry-fink-ceo-letter.

Castro, M. (2020), “Ecuador: polémica tras fusión del Ministerio del Ambiente con Secretaria del Agua”, 17 March [online] https://es.mongabay.com/2020/03/ecuador-fusion-ministerio-del-ambiente-senagua-polemica.

Diario Oficial de la Federación (2020), “DECRETO por el que se establecen las medidas de austeridad que deberán observar las dependencias y entidades de la Administración Pública Federal bajo los criterios que en el mismo se indican” [online] https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5592205&fecha=23/04/2020.

ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2020a), “Addressing the growing impact of COVID-19 with a view to reactivation with equality: new projections”, COVID-19 Special Report, No. 5, Santiago, July.

_(2020b), “Recovery measures for the tourism sector in Latin America and the Caribbean present an opportunity to promote sustainability and resilience”, COVID-19 Reports, Santiago, July.

_(2019), (2019), “SDG 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development in Latin America and the Caribbean” [online] https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/static/files/sdg14_c1900732_web.pdf.

Ecuador TV (2020), “Entrevista a René Ortiz, Ministro de Energía y Recursos Renovables” [online] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7S6pHAfSt14&feature=youtu.be&t=825.

El País (2020), “Crean Ministerio de Ambiente y cesan a trabajadores de la Dinama”, 6 June [online] https://www.elpais.com.uy/informacion/politica/crean-ministerio-ambiente-cesan-trabajadores-dinama.html.

Farmer, D. and others (2020), “Supply and demand shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic”, CEPR Covid Economics, 17 April.

Gottdenker, N.L. and others (2014), “Anthropogenic land use change and infectious diseases: a review of the evidence”, EcoHealth, vol. 11.

ICT (Costa Rican Institute of Tourism) (2020), “Metadatos de divisas por concepto de turismo” [online] https://www.ict.go.cr/en/documents/estad%C3%ADsticas/cifras-econ%C3%B3micas/costa-rica/960-divisas-por-concepto-de-turismo/file.html.

INE (National Institute of Statistics)/Office of Tourism (2020), Barómetro de Turismo junio 2020 [online] http://www.subturismo.gob.cl/barometros/.

INEGI (National Institute of Statistics and Geography) (2020), Datos de Turismo [online] https://www.inegi.org.mx/temas/turismo/

JMP (WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene) (2020), The JMP Global Database [online database] https://washdata.org/data/household#!/table?geo0=region&geo1=sdg.

López-Feldman, A. and others (2020), “Environmental impacts and policy responses to COVID-19: a view from Latin America”, Environmental and Resource Economics, 13 July.

Molina, J. (2020), “La pandemia pone freno a prohibiciones al plástico de un solo uso en EE.UU. y en Chile gobierno se abre a fijar excepción temporal” [online] https://www.paiscircular.cl/industria/covid-19-y-regulaciones-a-plasticos-de-un-solo-uso/.

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) (2020), “COVID-19 and the food and agriculture sector: issues and policy responses”, 29 April [online] https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=130_130816-9uut45lj4q&title=Covid-19-and-the-food-and-agriculture-sector-Issues-and-policy-responses.

Pearson, R. and others (2020), “COVID-19 recovery can benefit biodiversity”, Science, vol. 368.

Pizarro, C. (2020), “Gobierno espera reactivar proyectos por US$ 20 mil millones en próximos siete meses”, La Tercera [online] https://www.latercera.com/pulso/noticia/gobierno-espera-reactivar-proyectos-por-us-20-mil-millones-en-proximos-siete-meses/IFB2W2XKMZBIHPPXIZJM6HZ6UM/.

Rajao, R. and others (2020), “The rotten apples of Brazil’s agribusiness”, Science, vol. 369, No. 6501.

Suzán, G. (2020), “Webinar: Pandemia y naturaleza. La relación entre el COVID 19 y nuestro impacto ambiental”, WWF México, 7 May.

Waldron, A. and others (2020), “Protecting 30% of the planet for nature: costs, benefits and economic implications. Working paper analysing the economic implications of the proposed 30% target for areal protection in the draft post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework” [online], https://www.campaignfornature.org/protecting-30-of-the-planet-for-nature-economic-analysis.