Basic water and electricity services as key sectors for transformative recovery in Latin America and the Caribbean

Work area(s)

1. Gaps in access to drinking water and electricity in Latin America and the Caribbean

a. Energy insecurity and its impact on people

Currently in Latin America and the Caribbean, 17 million people lack access to electricity and 75 million to clean cooking fuels and technologies, a situation that has exacerbated poverty and vulnerability during and since the pandemic and that may be exacerbated by rising fossil fuel prices in the context of the war in Ukraine. This energy insecurity is having physical, social and economic impacts on millions of people across the region (ECLAC, 2022).

The economic and social dimensions are directly related to lack of access to energy services or affordability problems, i.e., to families not having access because there is no infrastructure for it or because they cannot afford to pay for this service as they have other priorities, such as food, health care, etc.

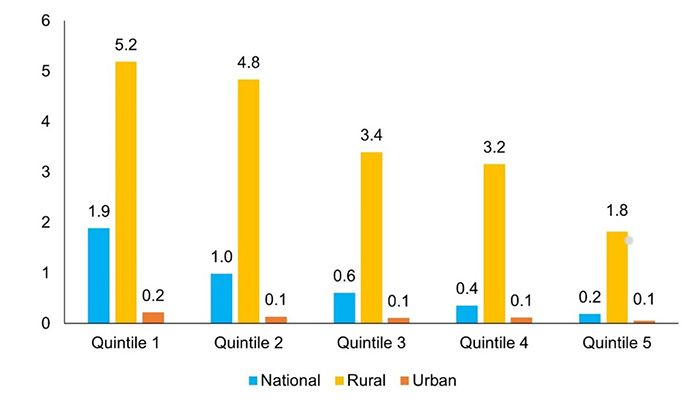

Figure 1

Latin America and the Caribbean (16 countries): proportion of the population without access to electricity, by income quintile (rural, urban and total), latest year availablea

(Percentages)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of the latest household surveys.

a 2017 for Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Paraguay, Peru, the Plurinational State of Bolivia and Uruguay; 2016 for the Dominican Republic, Honduras and Mexico; 2014 for the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Guatemala and Nicaragua.

Figure 1 shows the proportion of the population in Latin America and the Caribbean without access to electricity by income quintile. It can be seen that the rural population has less access to electricity in all quintiles. The data indicate that indigenous and Afrodescendent populations are also among the most vulnerable. In the region, the proportion of the indigenous and Afrodescendent population without access to electricity is twice and sometimes three times as high on average as the proportion of the non-indigenous and non-Afrodescendent population.

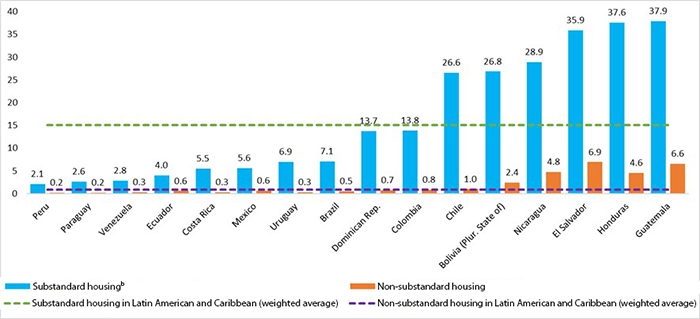

In Latin America and the Caribbean, an average of 15% of the population living in substandard housing has no access to electricity (figure 2). However, this share is higher in Chile, El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua and the Plurinational State of Bolivia, where between 30% and 40% of those living in substandard conditions do not have access. All these people live in informal settlements under conditions that do not satisfy their right to decent housing. The physical dimension of access to electricity includes not only the poor quality of housing but also the structure of the home environment and inefficient and dilapidated appliances.

Figure 2

Latin America and the Caribbean (16 countries): proportion of the population without access to electricity, by standard of housing, latest year availablea

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of the latest household surveys.

a 2017 for Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador, Paraguay, Peru, the Plurinational State of Bolivia and Uruguay; 2016 for the Dominican Republic, Honduras and Mexico; 2014 for the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Guatemala and Nicaragua.

b ECLAC defines a substandard home as one lacking certain materials. Also included here are households living in homes where the roof, walls or floor are made from irrecoverable materials, e.g., earth floor or walls and/or roof made from natural fibres and/or waste materials.

One consequence of lockdown measures in Latin America and the Caribbean was substantial job losses that limited the resources available for people to pay their electricity bills. This situation may worsen, especially in countries of the region where electricity tariffs are high and where they increased during the pandemic, and as a consequence of the rise in fossil fuel prices in the current war context. Similarly, consideration needs to be given to the energy dependence of the water supply, which is also affected by rising fuel prices. In the region, the energy costs of drinking water and sanitation service providers can amount, on average, to 40% of all operating expenses (Ferro and Lentini, 2015). It is therefore important to take these factors into account to ensure that the basic residential energy and water needs of the region’s citizens are met, especially if their incomes have been negatively affected by the impact of COVID-19.

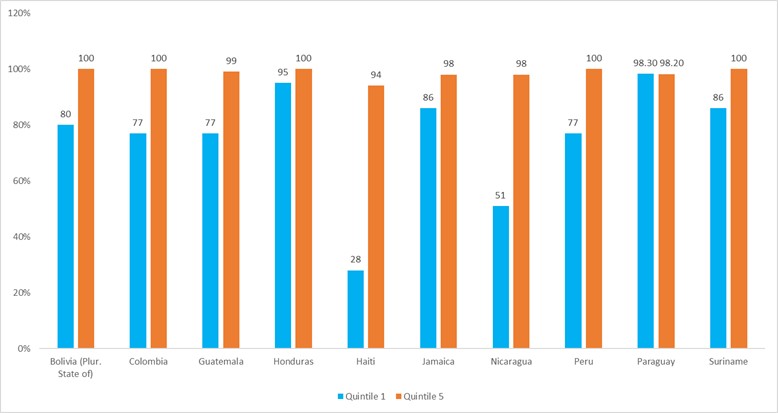

b. Inequality in access to safe drinking water has increased people’s vulnerability

In the region, 161 million people (equivalent to 2.5 out of every 10) do not have adequate access to safely managed drinking water. Even more seriously, 431 million people (equivalent to 7 out of every 10) in the region do not have access to safely managed sanitation. Furthermore, most of these people belong to the most vulnerable quintiles. Differences in access between the most vulnerable quintile and the highest-income quintile average more than 20% (figure 3) and are much more substantial in some countries of the region.

Figure 3

Latin America and the Caribbean (10 countries): access to basic drinking water services, 2017

(Percentages of the population)

Source: WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene, 2022.

An average of 0.8% of household spending goes on drinking water in the Latin America and Caribbean region as a whole. An analysis by quintiles, however, shows that the lowest-income quintiles can pay up to 2.5 times as much as the wealthiest quintiles. This is because many households do not have direct access to drinking water, so they have to buy it bottled or from tanker trucks. In Cochabamba in the Plurinational State of Bolivia, for example, water supplied by tanker truck costs 4 times as much as piped water (Mitlin and others, 2019), while in Peru it can cost up to 12 times as much (World Bank, 2015). Additionally, water quality is often inferior (Mitlin and others, 2019). Higher-income households not only spend proportionally less (0.6% of their budgets) but consume more in absolute terms than the other quintiles. Indeed, in Latin America and the Caribbean, the two richest quintiles account for half of total consumption.

Although this may seem a small percentage of household expenditure, rising unemployment and a reduction in income resulting from the pandemic and exacerbated by the war in Ukraine may leave households unable to afford basic services.

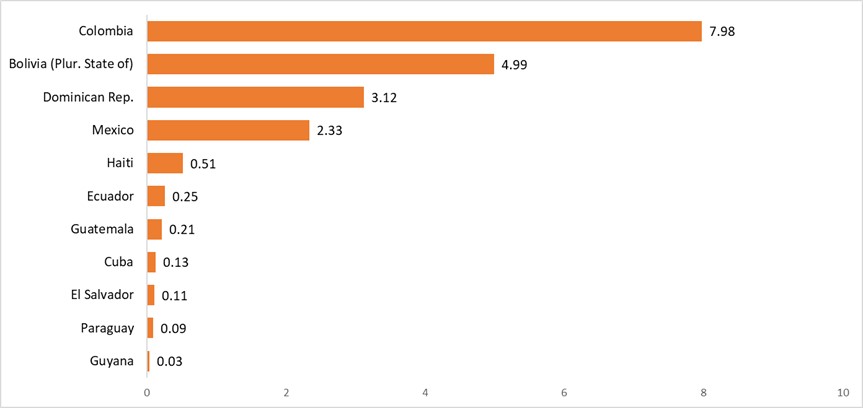

To better understand the risk of being impacted by COVID-19 and its relationship with drinking water, it is necessary to analyse two things: exposure and vulnerability. Some 80% of the population in Latin America and the Caribbean live in cities, where social interactions are more intense and therefore exposure to infection is higher. Millions of people in Latin American and Caribbean cities lack access not only to safe drinking water, but also to handwashing facilities: more than 9 million people in Colombia, almost 5 million in the Plurinational State of Bolivia and 2 million in Mexico (figure 4). In contrast, vulnerability is generally higher in rural areas, given the weakness not only of drinking water and sanitation infrastructure but also of health infrastructure.

Figure 4

Latin America and the Caribbean (11 countries): people without access to handwashing facilities in cities, 2018

(Millions of people)

Source: WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply, Sanitation and Hygiene, 2022.

2. Water and electricity policy proposals for a transformative recovery

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, palliative measures for the drinking water, sanitation and electricity sectors were taken in almost all countries of the region in early 2020, including reductions in bills and extension of payment deadlines, and/or disconnection moratoria. ECLAC has estimated the cost of these measures on the assumption that households in the two most vulnerable quintiles in 17 Latin American and Caribbean countries stopped paying their water and electricity bills for 6 months. On average, this estimate is in line with what happened during the pandemic, and it is a scenario that entails revenue losses for providers, thus prejudicing the maintenance of basic service infrastructure. These losses are estimated to amount to an average of 0.4% of regional GDP, requiring subsidies or preferably investment by the State to compensate for them.

While these measures were effective in the emergency context, it was impossible to sustain them in the medium and long term, as they jeopardized the financial sustainability of the providers of these basic services. This shows the need to prioritize planned investments in the water and energy sectors to ensure they have resilient systems in place to cope with new scenarios such as the recent war in Ukraine.

Owing to the high vulnerability of members of the lowest-income quintiles, who are still struggling to pay their bills, especially energy bills because of the impacts of the war in Ukraine, ECLAC proposes a subsidy that can be adopted in the event that countries find themselves in such unstable situations:

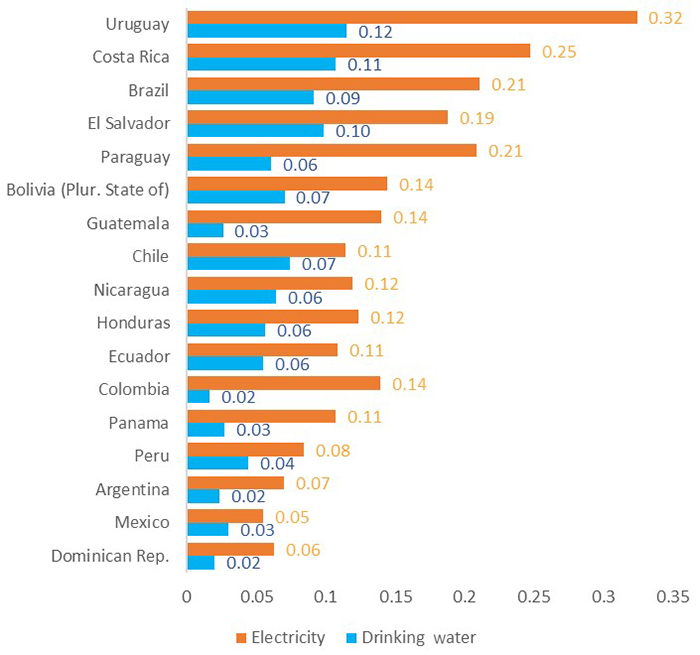

⚬ At the regional level, this subsidy to quintiles 1 and 2 for six months represents 0.06% of regional GDP for drinking water and sanitation and 0.14% for electricity services. Figure 5 presents the calculation of the estimated subsidy for six months by sector as a percentage of GDP in 17 countries of the region.

⚬ For the drinking water sector, the subsidy ranges from 0.02% of GDP in Argentina and Colombia to 0.12% of GDP in Uruguay.

⚬ For the electricity sector, the subsidy ranges from 0.05% of GDP in Mexico to 0.32% of GDP in Uruguay.

⚬ The subsidy to households in quintiles 1 and 2, which is also a liquidity mechanism for water and electricity service providers to ensure their medium- and long-term viability, is estimated at 0.2% of regional GDP.

Figure 5

Latin America and the Caribbean (17 countries): subsidies for drinking water and sanitation bills and electricity bills over 6 months

(Percentages of GDP)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of income and expenditure surveys and CEPALSTAT for GDP.

Note: Estimates based on the latest income and expenditure surveys available: 2004 for Honduras; 2006 for El Salvador and Uruguay; 2007 for Colombia, the Dominican Republic and Panama; 2008 for Brazil; 2011 for Paraguay; 2012 for Argentina, Chile and Mexico; 2013 for Costa Rica and the Plurinational State of Bolivia; 2014 for Ecuador, Nicaragua and Peru.

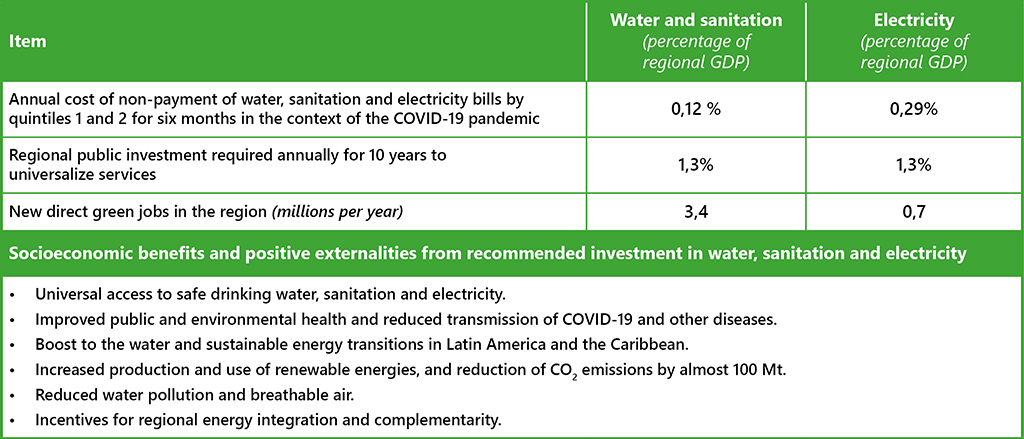

Public policy proposal: an investment push in water and energy is possible and cost-effective

Investing 2.6% of regional GDP annually over the next 10 years would be enough to universalize access to basic drinking water, sanitation and electricity services, leaving no one behind. In addition, it would reduce infections from COVID-19 (and other diseases), while driving recovery from the pandemic and the geopolitical crisis that has led to inflation and stagnation in the region, creating up to 4.1 million direct green jobs per year. In addition, it would reduce pollution and incentivize the transition to greater use of renewable energy (box 1).

In the water and electricity sectors, which are essential for society, it is essential to strengthen institutions and planning and regulatory bodies that can ensure universal access to these services with quality for all citizens at all times. This is particularly important in emergency situations, such as the pandemic, in difficult global geopolitical processes such as the war in Ukraine, and in the event of disasters such as earthquakes, floods and other extreme phenomena that hit the most vulnerable sectors and informal settlements hardest. It is important to avoid improvisation and to urgently implement risk prevention and management and emergency management mechanisms, including risk management, public education and information strategies and instruments and measures to increase resilience and adaptive capacity, e.g., through reserve funds, insurance or increased capacity to protect citizens from such crises. Policy interventions are thus needed to guarantee the accessibility, affordability and quality of water and electricity services in the short and long terms. Such policies should place special emphasis on vulnerable populations, minimize social inequality and use renewable energy sources and cleaner technologies.

Accordingly, the context of the post-pandemic recovery in the midst of the hydrocarbon and food price crisis is an opportunity to review operating and investment plans in these two basic service sectors, as they represent major opportunities for economic revival in the region.

As a post-pandemic recovery proposal, it is essential that the countries of the region should give priority in their economic stimulus packages to investments designed to close coverage gaps in the drinking water, sanitation and electricity sectors, as well as to improve energy efficiency in both sectors and make services cleaner and more sustainable. This type of investment represents a great opportunity to improve the social conditions of vulnerable segments, generate green jobs and promote the use of more sustainable technologies, which will ultimately contribute to the revival of the regional economy.

As a supporting measure, it is hoped that cooperation agencies and international and regional banks will prioritize and focus their efforts on this type of investment, which has high socioeconomic and environmental returns and also contributes to post-pandemic recovery. Estimates for closing coverage gaps in basic services are as follows:

• In the electricity sector, including the use of renewable technology (i.e., solar and wind) in line with SDG 7 targets, 1.3% of regional GDP should be invested annually for 10 years (ECLAC, 2021).

• To achieve universalization (and improve access, quality and efficiency) for drinking water and sanitation services in the medium and long term, including wastewater treatment (SDG 6 targets), 1.3% of regional GDP needs to be invested annually for 10 years (ECLAC, 2021).

These investments will bring great benefits, since they will help to generate green jobs, improve health, cut poverty and reduce environmental pollution.

In the case of the electricity sector, investments aimed at closing the coverage gap can bring the following benefits and opportunities:

• In light of the impacts of COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine, the region should target its economic stimulus packages on the development of sustainable, renewable and clean energy infrastructure throughout the value chain. These actions are not only an opportunity to generate thousands of new jobs, but also a fundamental precondition for a greener and more sustainable economic recovery.

⚬ Just investing to close the electricity access gap in Latin America and the Caribbean could generate up to 700,000 new skilled and unskilled jobs1 in the region over the next 10 years.

⚬ Moreover, if the entire value chains of the renewable industry were to be located in Latin America and the Caribbean, just manufacturing the solar panels and wind turbines needed to achieve this would represent almost 1 million more jobs2 for the region between 2020 and 2030.

• To secure energy services during periods of crisis (pandemics, wars, disasters such as droughts, storms, earthquakes or tsunamis), it is imperative for policymakers to recognize the benefits of energy complementarity3 and integration at the regional level, including more reliable supply and more stable electricity prices, with these benefits extending to those countries in the region with lower shares of hydropower in their energy mix.

• In terms of environmental benefits, using renewable energy to close the electricity coverage gap would mean 100 million tons less CO2 emissions than if the gap were closed with traditional technologies such as natural gas and diesel.

In the case of drinking water and sanitation, the benefits of these investments are:

• In respect of job creation, the investment of 1.3% of regional GDP annually over the next 10 years would make it possible to universalize access to safely managed drinking water and sanitation, thus honouring the human right to these services while also yielding numerous socioeconomic and environmental benefits. Economically, this could generate up to 3.4 million jobs per year in construction, maintenance and operation.

• In respect of public health, closing the coverage gap is essential for the containment of COVID-19 and other pandemics and endemics, as it ensures that the population has water for cleaning tasks and frequent handwashing. Without effective control of the pandemic, economic recovery cannot begin (ECLAC/PAHO, 2020). Likewise, continuous access to high-quality drinking water results in a lower incidence of diseases associated with lack of access to this natural resource, which represents a major socioeconomic burden and weakens human capabilities. In fact, it was estimated in 2016 that 5.7 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) with a value of US$ 1.8 billion had been lost in the region because of such diseases4.

• In the social sphere, i.e., as regards the cost to the most vulnerable, paying for piped drinking water reduces the regressivity currently represented by the financial effort that households have to make when they do not have access to it and must resort to tanker trucks or other more costly mechanisms.

• Where environmental benefits are concerned, closing the gap in drinking water and sanitation coverage will help to restore many water bodies polluted by untreated wastewater. In Latin America, about a quarter of river reaches are affected by severe pathogenic pollution, with monthly flow concentrations of faecal coliform bacteria of more than 1,000 CFU/100 ml, the figure having increased by almost two thirds between 1990 and 2010 (UNEP, 2016). Nature-based solutions for wastewater treatment could be of the utmost value to the region. One example of this is human-made wetlands, which allow organic matter and pathogens to be reduced through natural processes and which are also among the world’s most productive ecosystems, providing nitrogen-rich water for crop irrigation, biomass and biogas for energy production (UN Water, 2018). These wetlands can be managed by the community, meaning that local employment is also generated.

• Also, the use of technologies with a circular economy approach in the provision of drinking water and sanitation services can reduce not only water pollution but also air pollution by reducing emissions of methane, which is 25 times as polluting as CO2. For example, the investments that ECLAC estimates are needed to convert 75 wastewater treatment plants serving 33 million people in Latin America and the Caribbean have a positive benefit-to-cost ratio of 1.34.

• In summary, the benefits of universalizing access to safe drinking water and sanitation exceed the associated costs by a factor of at least three globally (Hutton and Varughese, 2016). In the Latin America and Caribbean region, the cost-benefit ratio is 2.4 for drinking water and 7.3 for sanitation (WHO, 2012).

Table 1

Latin America and the Caribbean (18 countries): summary of investment required to universalize drinking water, sanitation and electricity coverage and its benefits

1 Calculated by ECLAC on the basis of the deployment of solar, wind and biomass technologies. Includes construction, installation, operating and maintenance costs. A total of between 4,055,000 and 6,375,000 million new jobs is estimated for the period 2020-2030.

2 Calculated by ECLAC, on the basis of solar and wind technology manufacturing requirements.

3 In this respect, the complementarity of hydropower and other renewable energy sources offers great advantages, e.g., during seasons of low rainfall the short-term variability of solar and wind energy can be used cost-effectively through the flexible operation of hydropower. The long-term use of a combination of hydropower and other renewable energy technologies will produce an electricity system better able to cope with the impacts of climate change and the variability of climate phenomena such as El Niño and La Niña.

4 Based on estimates by Dalal and Svanström (2015), who report worldwide economic losses due to loss of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) at 848 billion in 2014, equivalent to US$ 326 per DALY.

Bibliography

Dalal, K. and L. Svanström (2015) “Economic Burden of Disability Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) of Injuries”, Health, No. 7, 27 April.

ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2022), Repercussions in Latin America and the Caribbean of the war in Ukraine: how should the region face this new crisis?, 6 June.

_(2021), “The recovery paradox in Latin America and the Caribbean. Growth amid persisting structural problems: inequality, poverty and low investment and productivity”, Special Report COVID-19, No. 11, Santiago, July.

ECLAC/PAHO (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean/Pan-American Health Organization) (2020), “Health and the economy: A convergence needed to address COVID-19 and retake the path of sustainable development in Latin America and the Caribbean”, ECLAC-PAHO COVID-19 Report, Santiago, July.

Ferro, G. and E. Lentini (2015), “Eficiencia energética y regulación económica en los servicios de agua potable y alcantarillado”, Natural Resources and Infrastructure series, No. 170 https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/37630/S1421127_es.pdf?sequence=1.

Hutton, G. and M. Varughese (2016), “The costs of meeting the 2030 Sustainable Development Goal targets on drinking water, sanitation and hygiene”, World Bank Group Water Sanitation Program (WSP), technical paper, Washington, D.C., January.

Mitlin, D. and others (2019), “Unaffordable and undrinkable: rethinking urban water access”, Working Paper, Washington, D.C., World Resources Institute.

Hulton, G. and WHO (World Health Organization) (2012), Global costs and benefits of drinking-water supply and sanitation interventions to reach the MDG target and universal coverage (WHO/HSE/WSH/12.01).

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) (2016), A Snapshot of the World’s Water Quality: Towards a global assessment, Nairobi.

UN Water (United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction) (2018), 2018 UN World Water Development Report, Nature-based Solutions for Water.

WHO (World Health Organization) (2012), Global Costs and Benefits of Drinking-Water Supply and Sanitation Interventions to reach the MDG Target and Universal Coverage, Geneva.