Malnutrition among children in Latin America and the Caribbean

Work area(s)

Teaser

Proper nutrition is a fundamental element in the realization of children’s right to enjoy the highest attainable level of physical and mental health.

Proper nutrition is a fundamental element in the realization of children’s right to enjoy the highest attainable level of physical and mental health. Malnutrition, in all its forms, undermines human development, has a negative impact on social and economic progress and hinders the exercise of human rights in many different ways. The sustained burden of malnutrition among women and children in the Latin American and Caribbean region is impairing the ability of these countries to achieve at least eight of the Sustainable Development Objectives.[1]

Malnutrition, which includes underweight and stunting[2] and overweight and obesity, has various causes and consequences. At least three fields of analysis are involved in arriving at a full understanding of malnutrition and its causal factors. The first focuses on food security, which has to do with whether or not the entire population has physical, economic and social access to a supply of safe, nourishing food, and vulnerability in terms of the probability and/or risk that food consumption or access to food may be diminished as a result of the population’s living conditions and response capacity. The second relates to the demographic, epidemiological and nutritional transitions that have altered the impact of food-related issues. Today, changes in the age structure of the population, consumption decisions, lifestyles and levels of activity and the interrelationships among these factors have modified people’s nutritional needs. The third and final area of analysis has to do with the life cycle and the key role that it plays in this respect, since nutritional problems and their effects are factors throughout people’s lives, starting from the moment they are born (Martínez and Fernández, 2006).

Although rates of undernutrition in the region have been more than halved since 1990, the levels of undernutrition and anaemia remain high in many countries, and national averages often conceal sharp differences between geographic areas or between populations groups with differing levels of education and incomes or different ethnic backgrounds. In addition, the region is witnessing rising levels of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents.

1.Malnutrition in the region

Malnutrition leads to death in some cases and has long-term effects on those who survive it as well. For more than two decades, the region has been working to tackle the problem of undernutrition among children subject to underweight and/or stunting during their early years of life. The situation has been further complicated by an increase in the number of people of all ages who are overweight or obese and by the evidence regarding micronutrient deficiencies. Globalization and rising income levels have altered people’s eating habits and lifestyles. Increased consumption of processed foods and greater sedentarism are just some of the factors that are posing new types of health policy challenges.

Undernutrition

The process of nutrition begins during gestation, and an infant’s weight at birth is an indicator of both the newborn’s and the mother’s nutritional and health status. Although the incidence of low birthweights (undernutrition) has been reduced, over 10% of children suffer from low birth weight and 5% of these children exhibited intrauterine growth restriction at birth.[3] According to data compiled by the World Health Organization (WHO), children who weigh less than 2,500 grams at birth are at a greater risk of death.

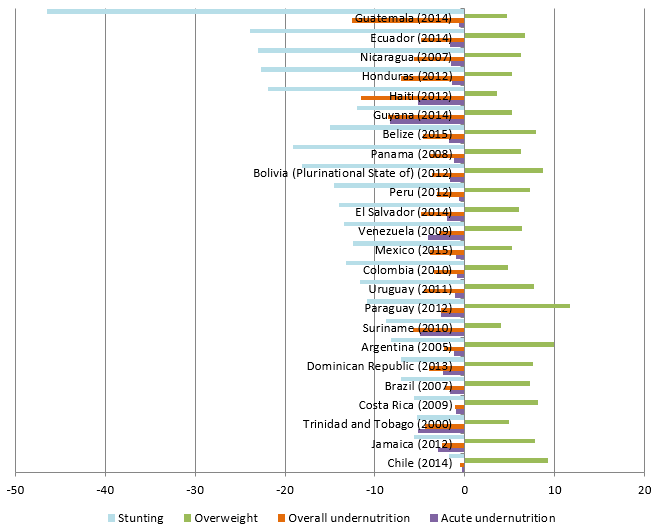

In the case of malnutrition caused by micronutrient deficiency, the three most commonly used anthropometric indicators are low weight for age, or underweight; low height for age, or stunting; and low weight for height, or acute undernutrition. Undernutrition rates in the region vary widely. For example, as shown in figure 2, the underweight prevalence in Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Jamaica are under 2.5%, whereas, at the other extreme, over 10% of the children in Guatemala, Guyana and Haiti are underweight. Stunting is a problem in most (67%) of the countries and, overall, 10% of the population —more than 7 million children— fall into this category.

Disparities exist within countries as well as between them. For example, in Peru, as of 2014 there was a sharp gap between different areas of the country, with the stunting prevalence standing at 54.6% in Huancavelica but at just 3% in Tacna (Martínez and Palma, 2014). These differences are also reflected in the results of the 2016 National Demographic and Health Survey, which indicate that the rate in Tacna was 2.3%, while it was 33.4% in Huancavelica (INEI, 2016). In Ecuador, sharp differentials were also recorded in that same year, with the highest prevalence being in Chimborazo Province, where the prevalence of low height for age totalled 52.6%, and the lowest in El Oro Province (15.2%) (Martínez and Palma, 2014).

Food and nutrition security for the indigenous population is another key factor. As noted in the 2016 Social Panorama of Latin America (ECLAC, 2017), indigenous children are at the greatest disadvantage. Information for seven countries in the region from around 2010 indicates that “prevalence of stunting is over twice as high for indigenous children under five as for the non-indigenous children, ranging from 22.3% in Colombia to 58% in Guatemala. Ethnic disparities are even wider in the case of severe stunting, while overall undernutrition behaves similarly” (ECLAC, 2017, p. 150).

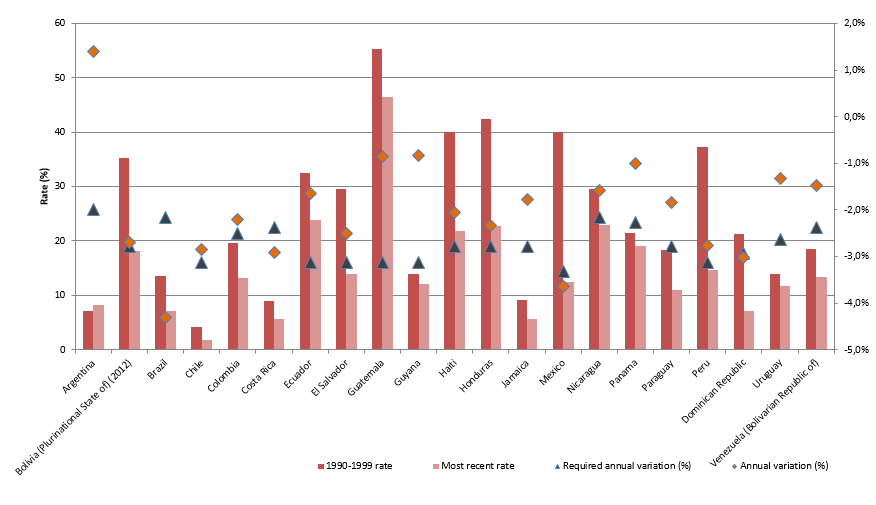

Definite progress has been made, however (see figure 1). Since 1990, the countries of the region have lowered the prevalence of stunting by an average of 40%. Mexico, Peru and the Dominican Republic have made particularly strong headway, as they have cut their 1990 rates of 40.1%, 37.3% and 21.2%, respectively, by over 60%. The country that currently has the highest prevalence is Guatemala, where more than 46.5% of the child population, or nearly 900,000 children, fall into this category. Consequently, although advances have clearly been made, further efforts will be required to attain the Sustainable Development Goal of putting an end to hunger and to all forms of malnutrition by 2030. The greatest challenge in this respect is being faced by Argentina and Guyana, since, according to the available data, the rates of undernutrition in these two countries have risen since 1990.

Figure 1

Latin America (21 countries): stunting rates and variations, 1990-latest available data

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional en América Latina y el Caribe [online database] http://dds.cepal.org/san/estadisticas; on the basis of World Health Organization (WHO) data and official country reports.

According to Galasso and Wagstaff (2017), stunting in the countries of the world is not being reduced fast enough to attain the targets set for the Sustainable Development Goals, and a discussion is therefore called for regarding the types of policies and programmes required in order to reduce the rate more quickly. Figure 1 depicts calculations of the average annual reduction that would be necessary in order to halve stunting by 2030. The countries of the region that are closest to reaching that benchmark are Brazil, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic and Mexico; the rest will have to redouble their efforts to speed up the rate of reduction in stunting in order to meet the Goal.

Overweight and obesity

At the other extreme, the increase in the number of overweight and obese children is alarming. The consequences and effects of these conditions are seen while the affected children are growing, but they are also evident after they reach adulthood. In the region, the percentage of children between 0 and 4 years of age who are overweight is on the rise. As is shown in figure 2, with the exception of Haiti, the rate for this age group at the regional level amounts to 7%, which means that nearly 4 million children under the age of 5 are either overweight or obese.

The rates for the school-age population are even higher than for children under 5 years old. According to statistics compiled by the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO, 2014), the rates for children from 6 to 11 years of age in the countries for which information is available range from 15% in Peru to 34.4% in Mexico, and the rates for children between the ages of 12 and 19 vary from 17% in Colombia to 35% in Mexico. While there is information for some countries, greater efforts will be required to compile sufficient data on the nutritional status of school-age children and adolescents at the regional level.

Figure 2

Latin America (24 countries): stunting, underweight and acute undernutrition and overweight among children under 5 years of age, by country

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Seguridad Alimentaria y Nutricional en América Latina y el Caribe [online database] http://dds.cepal.org/san/estadisticas; on the basis of World Health Organization (WHO) data and official country reports.

The combination of nutritional problems caused by excess weight and by undernourishment (“the dual burden of malnutrition”) is a recent development in the region which merits greater attention, since it is a reflection of inequalities within families, households and countries. As early as the year 2000, Doak and others (2000, 2005) found that 11% of Brazilian households exhibited both problems. In Colombia, the Food and Nutritional Security Observatory (OSAN, 2014) defines this dual burden as the existence in the same household of an overweight or obese adult and a child suffering from undernutrition. At the national level, this dual burden is present in 8.2% of all households, but the rate in some departments is over 15% (in Amazonas, Guainía, La Guajira and Vaupés). Barrios de León and others (2013) conducted a study in the municipality of Huitán in Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, and found that nearly 65.4% of the children there suffered from stunting and that a dual burden was present in 12.7% of the households.

These findings show that the region must not only tackle the problem of undernutrition, but also must address the rising rate of obesity in the child and adolescent population without delay by developing programmes and policies to foster healthy lifestyles as a means of safeguarding children’s rights. The dual burden of malnutrition poses a new nutrition policy challenge for the countries of the region, which will have to work to put an end to all forms of malnutrition, without leaving anyone behind.

Hidden hunger in the region: a challenge to be metMicronutrient deficiency is a form of “hidden hunger” whose prevalence in the region has reached worrisome levels. Unlike the case of a lack or shortage of food, micronutrient deficiencies do not have any visible physical effect but may nonetheless have a negative impact on a population, since micronutrients support a wide range of bodily functions. Micronutrients that play a key functional role in children’s growth and development and in the health of adults include iron, vitamins A, B and D, calcium and zinc.While reliable data for assessing micronutrient deficits in the child population are lacking, the most recent World Health Organization (WHO) studies indicate that iron-deficiency anaemia is present in over 35% of the children between 6 and 59 months of age in the region. In Haiti and the Plurinational State of Bolivia, over 60% of all children suffer from anaemia. Cediel and others (2015a) reviewed the available information in the region on zinc deficiencies and found a high rate of deficiency in this micronutrient in some countries. For example, in Mexico the zinc deficiency rate amounted to 25.3% among children between 6 months and 11 years of age, while the rate for children under 6 years of age in Colombia was 26.9%. These researchers also found differentials between the indigenous and non-indigenous populations, with the former suffering the most from this problem in Colombia and Guatemala. Their estimates of the risk of zinc deficiencies make it clear that this is a public health problem that warrants further attention. Vitamin A deficiencies are also a public health problem, especially in Colombia, Haiti and Mexico, where the rate of that deficiency tops 24%. In this case, too, the deficiency rates are higher among indigenous groups and the Afrodescendent community than among the general population (Cediel and others, 2015b). Source: G. Cediel and others, “Zinc deficiency in Latin America and the Caribbean”, Food and Nutrition Bulletin, vol. 36, No. 2, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 2015a; ___“Interpretation of Serum Retinol Data from Latin America and the Caribbean”, Food and Nutrition Bulletin, vol. 36, No. 2, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, 2015b. |

2. The consequences of malnutrition

There is ample evidence of the consequences of undernutrition in terms of children’s skill acquisition, cognitive development, mortality rates and morbidity during their lifetimes. For several years now, the focus has been on learning more about the consequences of both nutritional deficiencies and overnutrition.

Low birthweight, which is also an indicator of undernutrition during pregnancy, is associated with a higher risk of death during the first months and years of life (Black and others, 2008 and 2013). This condition also affects the development of immunities during infancy and thereby heightens the risk of various types of infections that may cause disease or lead to death. Underweight, acute undernutrition and stunting also appear to be associated with an increased risk of death as a result of diarrhoea, pneumonia and measles (Black and others, 2013). Low birthweight and undernutrition during childhood are also risk factors for the development of non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

Victora and others (2008) maintain that stunting constitutes a risk factor for children’s overall development. Their review of a number of different studies leads them to conclude that delayed growth may be associated with short stature in adulthood, the completion of fewer years of schooling and a poorer cognitive performance. Recent studies have highlighted what happens to the brains of children suffering from stunting and the associated risk factors for impaired development. Many researchers have concluded that this is a problem that has lifelong consequences, given the nutrient requirements for proper brain development. The damage caused by undernutrition (low weight or slowed growth) at this stage of life is thought to have implications for brain structure and cognitive capacity (McCoy and others, 2016). For example, in a study of 79 countries, Grantham-Mc Gregor and others (2007) found that, for every 10% increase in stunting, the number of children who reached the last grade in primary school fell by 7.9%. Other studies in Brazil and Jamaica have yielded data that point to a correlation between stunting and poorer academic performance or lower levels of educational attainment (Hutchinson and others, 1997; Brito and de Onis, 2004). This reduction in cognitive capacity and in years of schooling will inevitably depress the income levels of persons who were undernourished during their childhood and, consequently, act as a constraint on the development of the societies in which they live.

The effects on children’s health and cognitive development translate into economic costs for the whole of society. In addition to the cost of health care occasioned by the need to treat related diseases or undernutrition itself, there is the cost of providing additional years of schooling for children who have to repeat grades because they have impaired attentions spans and learning capacity. These effects on health and educational attainment, in turn, lead to productivity losses. On the one hand, there is the loss of productivity equal to the loss of human capital associated with the lower level of educational attainment of persons who have been undernourished; on the other, there is the loss of production capacity occasioned by the number of undernutrition-related deaths (Martínez and Fernández, 2006).

In the case of overnutrition, overweight or obesity in childhood has both short- and long-term effects. Its short-run health risks include metabolic changes leading to high levels of cholesterol, triglycerides and glucose and the development of type 2 diabetes and high blood pressure. Some studies indicate that obesity during adolescence results in a higher-than-average risk of developing diabetes, asthma and respiratory problems (Cook and Jeng, 2009; Pulgarón, 2013). In the long run, obesity during childhood may be a risk factor for obesity in adulthood, along with its well-known consequences (Black and others, 2013). Between one third and one half of all obese children become obese adults (Rivera and others, 2014).

In addition to the direct effects on children’s and adolescents’ physical health, obesity and overweight affect their mental health as well. Obese or overweight children are more likely to suffer from psychosocial problems than their normal-weight peers because they are often stigmatized and become targets for taunting or intimidation (Cook and Jeng, 2009; Rankin and others, 2016).

The cost of malnutritionBoth the direct and indirect consequences of malnutrition have an economic cost. Its effects on people’s health make it necessary for them to invest in treatments for malnutrition itself and for associated illnesses. Its impact is also felt in the production sector, since it impairs people’s cognitive capacity and thus their future performance in the labour market. This is why it is useful to arrive at an estimate of its economic costs for society in terms of the amount of income that is lost or forgone as a result of malnutrition. Along similar lines of research, in 2017 ECLAC and WFP launched a new study aimed at calculating the cost of the dual burden of malnutrition. This study, which is the only one of its kind in the region, focuses on the cost of all forms of malnutrition by employing both the established methodology for estimating the cost of undernutrition and a new methodology for calculating the costs of overweight and obesity. The study found that the impact of malnutrition was equivalent to 4.3% of GDP in Ecuador, 2.3% in Mexico and 0.2% in Chile. The results showed that, for the year under study, health-related costs accounted for the largest share of the total cost in Chile, whereas, in Ecuador and Mexico, the largest percentage of the total corresponded to the loss of productivity caused by the effects of undernutrition. In Chile, since the rate of stunting is less than 2%, only the costs of obesity were estimated (Fernández and others, 2017). Horton and others (2010) have carried out studies that show that people who have been undernourished lose over 10% of their potential income during their lifetimes, which amounts to a loss of between 2% and 3% of GDP in many countries. In 2017, the World Bank analysed the cost of stunting for 140 countries in 2014 and found that, on average, per capita income was 5% lower in Latin America and the Caribbean for that year than it would otherwise have been.

Source: A. Fernández and others, “Impacto social y económico de la doble carga de la malnutrición: modelo de análisis y estudio piloto en Chile, el Ecuador y México”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2017/32), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2017; S. Horton and others, Scaling Up Nutrition. What Will It Cost?, Washington, D.C., World Bank, 2010; R. Martínez and A. Fernández, “The cost of hunger: social and economic impact of child undernutrition in the Plurinational State of Bolivia, Ecuador, Paraguay and Peru”, Project Documents (LC/W.260), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2009; R. Martínez and A. Fernández, “The cost of hunger: social and economic impact of child undernutrition in Central America and the Dominican Republic”, Project Documents (LC/W.144/Rev.1), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2008; R. Martínez and A. Fernández, “Modelo de análisis del impacto social y económico de la desnutrición infantil en América Latina”, ECLAC Handbooks, No. 52 (LC/L.2650-P), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2006. |

3. Preventing malnutrition

In order to work towards the fulfilment of the 2030 Agenda and to put an end to hunger and reduce malnutrition, progress needs to be made in the design and implementation of comprehensive multisectoral policies. The most successful efforts to combat malnutrition have been joint projects involving a number of different stakeholders that have taken into account all the various dimensions of nutrition issues rather than focusing exclusively on health issues (Martínez and Palma, 2014).

There is a wealth of programmatic evidence on the positive impact of different types of actions in terms of the reduction of undernutrition, including the studies compiled in a special series of The Lancet (2008 and 2013)[4] and the available data on the inroads made by national food and nutrition security policies in the region. Since nutrition-related problems have many different causes, lowering malnutrition rates requires coordinated action at different levels involving a variety of stakeholders in each country. In addition, sufficient resources have to be marshalled in order to reduce the vulnerability of the population groups that are at greatest risk throughout their lifetimes. In the cases of both undernutrition and overweight, the consensus view is that the focus should be on children between 0 and 24 months of age, since this internationally recognized “1,000-day window” is a key stage of life for the determination of optimum development. In the case of overweight and obesity, the period between 3 and 6 years of age is also crucial for inculcating healthy eating and exercise habits in order to foster proper growth. It is more difficult to change life habits when children are older, and school programmes and programmes for adolescents are therefore needed to address the risk factors associated with unhealthy behaviours. Cross-sectoral coordination is of critical importance in this respect, as effective measures for the prevention of malnutrition must encompass education, health, sports, sanitation and other factors that heighten vulnerability, such as poverty.

Martínez and Palma (2015) examine the existing evidence regarding two types of interventions —“specific” and “sensitive” interventions— for reducing malnutrition. Specific interventions focus on fetal development and children’s development during their early years of life, while sensitive interventions address underlying causes[5] of undernutrition. The latter type of intervention is a necessary one that works together with specific interventions to achieve greater effectiveness in the eradication of hunger. These measures involve a number of different sectors and are intended to have an impact in related areas, such as food production or poverty. In the latest issue of The Lancet, Ruel and Alderman and The Maternal and Child Nutrition Study (2013) discuss how sensitive measures can magnify the impact of specific interventions by creating a stimulating environment in which small children can grow and develop their maximum potential. The areas influenced by these measures include food production and access, food safety and quality, infrastructure, food aid, nutrition and health information and knowledge, and health care (Martínez and Palma, 2015).

Many of the region’s success stories concern initiatives that have had strong political backing. For example, Peru’s success in halving stunting between 2007 and 2014 was supported by the government’s commitment to the achievement of a series of targets and its policy for combating undernutrition through a results-based budgetary programme. In addition, an interministerial committee was set up to coordinate the multisectoral efforts needed to work towards that objective (Galasso and Wagstaff, 2017; Marini and Rokx, 2017).

Social protection policies and, in particular, cash transfer programmes (whether conditional or not) can help to increase food and nutrition security in the household. Nutrition indicators having to do with increases in household income and health conditionalities provide evidence of the positive impact of the PROGRESA programme in Mexico,[6] the Familias en Acción (families in action) initiative in Colombia[7] and the Bolsa Familia (family grants) programme in Brazil[8] (Martínez, 2015). In Peru, the issue of nutrition has been incorporated into JUNTOS, the country’s conditional cash transfer programme, with the introduction of two conditionalities relating to the health of children between 0 and 5 years of age and participation in the Food Supplements for High-Risk Groups Programme (PACFO) for children between 6 months and 2 years of age.

When designing such measures, the causes of obesity and undernutrition need to be taken into account, since, although some of the determinants of all types of undernutrition are the same, such as certain economic, social and environmental factors, there are also more immediate causes[9] that influence the body’s energy balance by creating an energy deficit or surplus, resulting in undernutrition or overweight. In the case of overweight or obese individuals, the causes of overnutrition entail an additional complexity when analysed from a life cycle perspective because it may also be linked to the effects of undernutrition during the early years of life (Fernández and others, 2017, p. 26).

Measures for preventing overweight and obesity therefore address the factors that may lead to weight gain and obesity, such as the excessive consumption of foods that are high in sugar, salt and fat and of sugary beverages and insufficient physical activity (PAHO, 2014). Many of these measures should focus mainly on doing away with unhealthy habits or reducing unhealthy behaviours and on encouraging healthy forms of consumption and behaviour in ways that take into account the associated factors, such as price, food production and marketing, and the availability and affordability of various products (PAHO, 2014).

The PAHO Plan of Action for the Prevention of Obesity in Children and Adolescents (PAHO, 2014) sets out the following strategic lines of action:

- Primary health care and promotion of breastfeeding and healthy eating.

- Improvement of school nutrition and physical activity environments.

- Fiscal policies and regulation of food marketing and labelling.

- Other multisectoral actions involving the private and non-governmental sectors (e.g. providing urban areas conducive to physical exercise and increasing the availability and accessibility of nutritional foods).

- Surveillance, research, and evaluation.

UNICEF also has a plan of action for reducing overweight and obesity in children that is based on three strategies:

- Compiling a stronger body of evidence by improving the data on young children and schoolchildren and the documentation of effective policies.

- Strengthening the regulations on labelling and on breast milk supplements, taxing sugary drinks and promoting nutritious foods.

- Building knowledge about nutrition and healthy eating habits.

Some countries in the region are already taking steps to counter the increased incidence of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents, including Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador and Mexico, where this problem is the most severe. Increased regulation of the advertising and marketing of unhealthy beverages and food products targeting children has been shown to have a strong impact. UNICEF (2015) conducted an exploratory study which showed that 31% of the Latin American and Caribbean countries have a total of 22 current policies on the regulation of the marketing and advertising of food and beverages for children. Of these 22 policies, 15 are focused on limiting the presence of certain food products in schools and only 2 restrict the use of characters, gifts or endorsements by famous people. The same study also notes that school kiosks sell unhealthy foods and that more than half of the schools studied display advertising materials from outside firms wishing to promote their products (such as sugary drinks or flavoured milk).

Food labelling regulations are also an effective tool for influencing adults’ and children’s decisions regarding the purchase of prepared foods. This type of strategy has been employed in Chile, Ecuador and Mexico (Institute of Public Health/UNICEF, 2016).

School meal programmes can also be used to address nutritional issues. Such programmes have been recognized as forming part of the benefits provided by social protection systems, and in recent years many of these services have been modified in order to align them with the needs of schoolchildren and changes in nutrition indicators. Meal programmes that were first introduced as a way of supplementing the diets of children from poor homes are being overhauled in countries with high levels of overweight and obesity in order to ensure that they offer nutritional foods and encourage children to adopt healthy eating habits. For example, in Brazil, at least 70% of the food provided by school meal programmes has to be natural or involve minimal processing (PAHO, 2014). School meal programmes are a key component of social protection systems since, by diminishing schoolchildren’s vulnerability, they help to safeguard the right to food and nutrition security and lower household food bills, thereby facilitating children’s access to school and increasing their ability to stay in school. These programmes also provide a way of linking in other social protection components, such as school scholarships, access to health services, emergency response actions during natural disasters and so forth.

Children’s right to healthy food and healthy lives is enshrined in a number of different international instruments, but the protection of that right is an enormous challenge. Preventive measures are urgently needed in order to address the problems of undernutrition and obesity and thus diminish the effects of malnutrition throughout the life cycle. Above and beyond the economic costs involved, deploying the measures needed to achieve this objective is an ethical imperative.

[1] For further information, see the United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition (UNSCN), "NUTRITION and the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Goals", Geneva, 2014 [online] https://www.unscn.org/files/Publications/Nutrition__The_New_Post_2015_S….

[2] Acute undernutrition: emaciation or low weight for height (wasting).

Underweight: low weight for age.

Chronic undernutrition or stunting: low height for age.

[3] See Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), "Core indicators" [online] http://www.paho.org/data/index.php/en/indicators.html.

[4] In 2008 and 2013, The Lancet ran two special series on maternal and child nutrition. See The Lancet, “Maternal and Child Nutrition”, 2013 [online] https://www.thelancet.com/series/maternal-and-child-nutrition; “Maternal and Child Undernutrition”, 2008 [online] https://www.thelancet.com/series/maternal-and-child-undernutrition.

[5] Underlying causes include socioeconomic, environmental and political/institutional factors that impact the mediate causes, such as nutrient absorption and the quantity and quality of food intake. For further details, see Martínez and Fernández (2006).

[6] See Gertler (2004).

[7] For further details, see Attanasio and others (2005).

[8] See De Brauw and others (2014).

[9] For further details, see Martínez y Fernández (2006).