Briefing note

The environmental impact of the prevailing development pattern endangers the well-being of much of humankind and, in some cases, its survival. That is why it is necessary to make deep transformations in the development paradigm and in the investments that make it possible, according to a new book published today by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

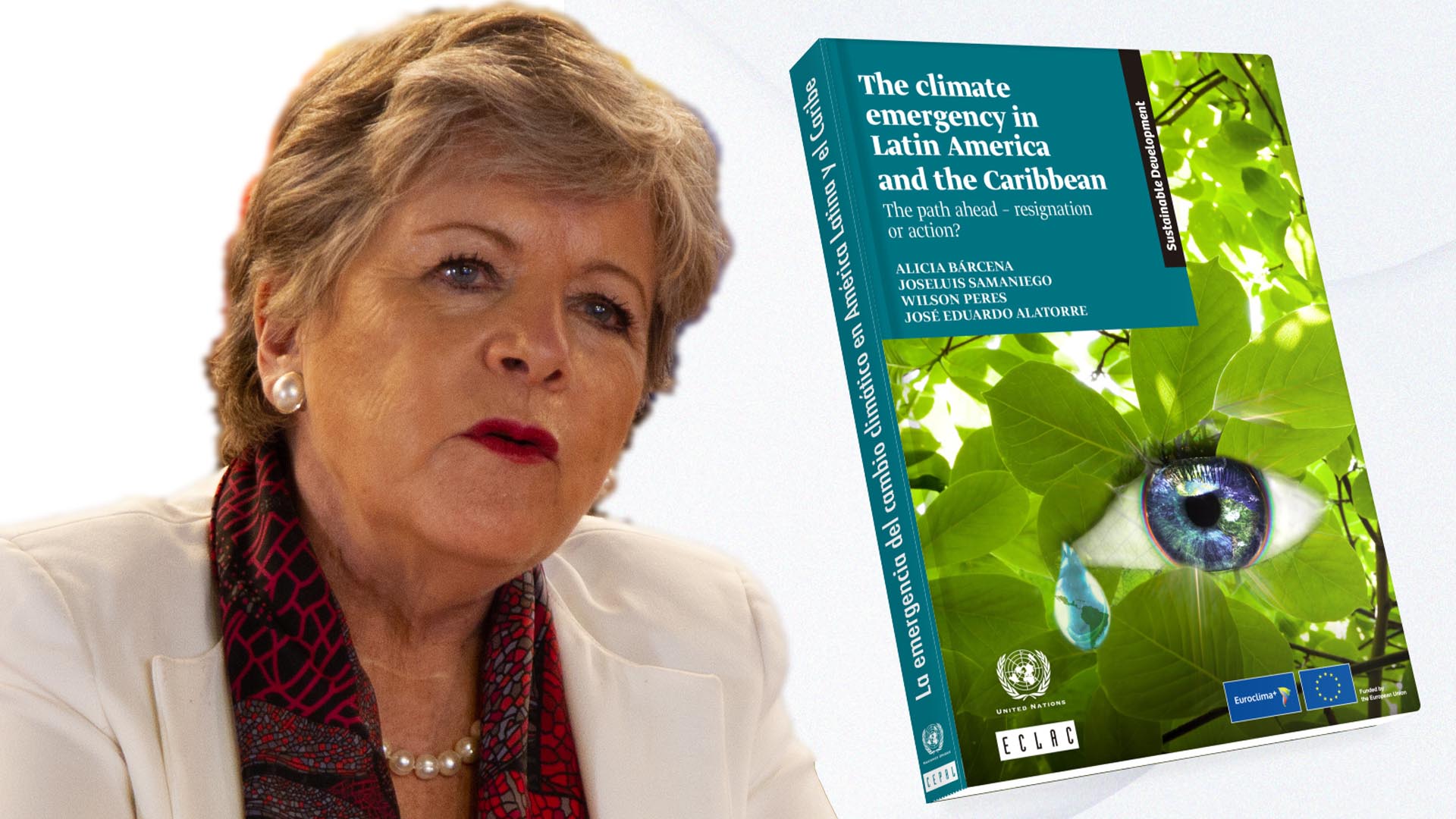

The publication – entitled The climate emergency in Latin America and the Caribbean: The path ahead – resignation or action? – was presented at a virtual conference by Alicia Bárcena, ECLAC’s Executive Secretary. António Guterres, the United Nations Secretary-General, sent a message for the occasion.

“The study that ECLAC is presenting today reflects more than a decade of research, follow-up and proposal building. It articulates a perspective from the regional level with the biggest global challenge of our time, climate change; and, as always, it does so by gathering together countries’ own assessments, their needs, and tracking their own responses, while also imagining and proposing more ambitious paths for action and revealing the urgency of providing greater responses,” the UN Secretary-General stated.

He added that “this book contributes notably to available knowledge, both for those in charge of designing and executing public policies as well as for our societies as a whole, which are essential protagonists in the change to production and consumption patterns that cannot be delayed any longer.”

Other speakers at the event included Teresa Ribera, the Fourth Vice-President of the Government of Spain and Minister for the Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge; Horst Pilger, Head of the Climate Change and Environment Section at the European Commission’s Directorate-General for International Cooperation and Development; Alfonso de Urresti, Chair of the Environment and National Assets Commission in the Chilean Senate; and Kishan Kumarsingh, Head of the Multilateral Environmental Agreements Unit of the Ministry of Planning and Development of Trinidad and Tobago and Co-Chair of the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action.

Also participating were Andrea Meza, Director of Climate Change at Costa Rica’s Ministry of Environment and Energy; Adriana Lobo, Executive Director of the World Resources Institute of Mexico and Colombia; João Carlos Ferraz, a scholar at the Federal University of Río de Janeiro; and the book’s co-authors: Joseluis Samaniego, Director of ECLAC’s Sustainable Development and Human Settlements Division; Wilson Peres, Senior Economic Affairs Officer; and José Eduardo Alatorre, an Economic Affairs Officer in the regional commission’s Economics of Climate Change Unit.

The publication exhaustively reviews the effects of the climate emergency in the Latin America and Caribbean region along with the policies used to tackle it. It proposes actions for a new, more sustainable and egalitarian development model, in line with the long-term vision of ECLAC and the 2030 Agenda. In addition, it sets out essential guidelines for reactivating with equality and sustainability.

The book indicates that the current health and climate crises are part of an unsustainable development model associated with a declining growth rate for production and trade, since even before this crisis, a recessionary bias and the decoupling of the financial system could be seen. This is a model linked to a high degree of inequality with dominance by elites, which is to say, the culture of privilege, and based on major negative externalities such as the emissions associated with climate change, which is exceeding global environmental thresholds, and with systemic vulnerabilities that have been exposed by COVID-19.

It warns that the crux of international negotiations and national policies alike is the struggle to divide, transfer, minimize, avoid and measure the burden of this externality.

In that sense, it indicates that the Paris Agreement defined the planet’s carrying capacity with regard to carbon emissions and established voluntary national carbon budgets via somewhat more ambitious, albeit still insufficient, Nationally Determined Contributions – among other advances. However, it involved a step backwards in terms of differentiating responsibilities between countries, which aggravates center-periphery tensions. “The remaining budget for the periphery may be insufficient for development needs,” the publication specifies.

The book sustains that Latin America and the Caribbean is a region that is extremely vulnerable to climate change because of its dependence on highly climate-sensitive activities, its low adaptive capacity and its exposure to various extreme hydrometeorological events.

It notes that between 1970 and 2019, Latin America and the Caribbean was affected by 2,309 natural disasters, according to figures from the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED). These events prompted 510,204 deaths, affected 297 million people and caused more than $437 billion dollars in damage.

The publication dedicates a special chapter to the cases of Central America and the Caribbean, two subregions that stand out because of their high degree of vulnerability to climate change and their limited participation in producing emissions, and which have climatic, geographic and socioeconomic particularities that justify a separate analysis. In the case of the Caribbean, the document analyzes ECLAC’s debt for climate adaptation swap initiative.

During the launch, Alicia Bárcena, ECLAC’s Executive Secretary, emphasized that in the face of the now unavoidable effects of climate change, one of the region’s priorities is to increase society’s resilience and adaptive capacity, while also exploring the existing synergies between adaptation processes and other development goals.

She noted that Latin America and the Caribbean has assumed adaptation and mitigation commitments that will be impossible to fulfill without structural change. To that end, ECLAC identifies policies for strategic sectors that reduce emissions, create jobs and boost investment, and would allow for undertaking the reactivation with equity and sustainability to move towards a new development pattern.

These sectoral drivers of structural change are non-conventional renewable energies, nature-based solutions, the circular economy and recycling, smart cities, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, less polluting consumption and the economy of care, she explained.

The senior United Nations official added that the response to the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) is an opportunity to move towards a big push for sustainability.

“We need a new development pattern aligned with the 2030 Agenda, we believe that building a welfare state in a new equation with the market and society is a matter of urgency. Strategies sustained over time are needed. This is a political undertaking to make the technical proposal viable and make room for science. Finally, we need institutions and coalitions that formulate and implement the policies, we need compacts at a global, regional, national and local level. The horizon is equality, progressive structural change is the path, and politics, the instrument,” she concluded.