A Strong Caregiving System for

a More Equal Society

The “economics of caregiving”, or simply “caregiving”, has been a topic of discussion for several years. The term refers to activities related to maintaining human life. Life is impossible without providing care.

Many women spend much of their time taking care of others, especially dependant persons. The sexual division of labour throughout centuries has been based on a social structure founded on families in which men are the providers and women are homemakers and caregivers. Women’s social struggle through the years has changed this, allowing them greater access to the labour market. However, another key demand for women is far from being met: recognizing women’s unpaid work.

This demand has come hand in hand with the pursuit of economic independence by women who rely on their spouse’s income or are single. In Latin America 29% of households are headed by women.

Three demands lay out the fragile state of women’s autonomy: the pursuit of independent income, greater political participation and control over their health and bodies.

These are the areas the Gender Equality Observatory of Latin America and the Caribbean is monitoring, as requested by ECLAC member countries.

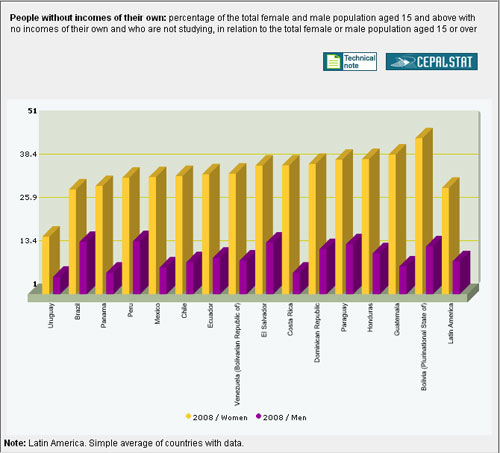

The situation in the Plurinational State of Bolivia is representative of the region. There, in spite of the progress made in women’s participation in the economy, 45.9% do not count with their own income (see graph 1). The situation is similar throughout the region to different extents and is aggravated when social protection systems are weak.

Population without own income per gender: percentage of men and women who do not receive income and are not students, per total of the non-student female and male population over 15.

Another common trait is the deficiency of care systems for small children, the elderly and the ill. Without a strong system that may facilitate women’s participation and permanence in the labour market, women often turn to relatives for alternative solutions.

To obtain a paid job many women must delegate the workload of domestic caregiving… to other women. In the private sphere, the circle of women’s care is made up of mothers, friends or neighbors of the delegating women, or by women who are hired and paid to provide that care.

Through time, the data shows that even though women have come to participate in the public sphere of society, they are still solely and exclusively in charge of the private sphere. Increasingly more, women with salaried employment continue to perform unpaid work, thus perpetuating the circle of caregiving by women.

This situation reveals how governments in the region consider caregiving policies to be of secondary importance. When these policies exist, they are benefits geared solely to women and not, in the case of caring for children, to both parents. This hampers or discourages women’s access to the labour market.

In the public sphere, caring for dependant members of society – children, the ill, the elderly or disabled- is also primarily a woman’s domain: nurses, teachers, pre-school educators, etc. Men continue dedicated mainly to productive activities, while women are concentrated in reproductive or caregiving activities, sometimes paid.

Until recently, women’s unpaid work was an invisible issue in society and national economies. However, several countries have taken steps to make it visible and acknowledge and compensate women’s domestic work. Over the past few years, some governments have conducted surveys on the use of time that reflect the total workload, measuring paid and unpaid work in society.

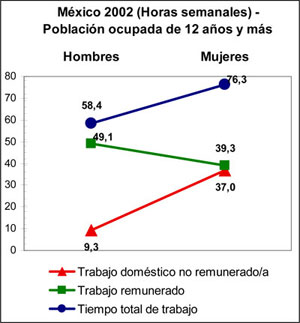

A study by ECLAC’s Division for Gender Affairs based on these surveys reveals two trends. One is that in every case, the total amount of time women spend working is greater than that spent by men. Secondly, also in every case, it is women who spend most of their time doing unpaid work.

In Mexico, for example, women work 27.7 more hours a week than men in unpaid domestic chores (see graph 2). This is an average of almost four hours a day more than men. In terms of total time spent working, women work 17.9 hours more than men. However, when it comes to paid jobs, men work almost 10 hours a week more than women.

This reflects the unequal workload between men and women, in addition to the inequalities associated with the type of work. Since domestic work and caregiving is not paid, it is easy to conclude that women, in every case, work more and make less than men.

The State, families and the market should be co-responsible for caring for dependant persons

in society. A key challenge to creating a more equal society is to recognize and redistribute unpaid work

through policies that facilitate men’s participation in caregiving (parental leave, universal childcare,

flexible schedules for men and women). In terms of social security, efforts could be made to deepen reforms

that acknowledge the time spent by women throughout their lives that explain their absence or irregularity in

paid jobs.

*by Division for Gender Affairs

More HEADLINES

Equality is an

Essential Value of the Development Agenda

![]()

| Data shows how women, in spite of participating in the public sphere, continue to be exclusively in charge of the private one. | |

| In Mexico, for example, women work 27.7 more hours a week than men in unpaid domestic work. | |

|

|